N is for Numerals |

|

|

|

|

Most stamps have numerals of some sort, indicating their value as postage, and all forms of numerals - Roman, Arabic, written - have been used on stamps somewhere.

The first US stamps had Arabic numerals on the five and Romans on the ten. At one time, Universal Postal Union regulations required that stamps used on international mail have Arabic numerals showing their home-currency value, so some U.S. stamps had to be modified to comply with that rule. If that rule still applied, issues such as the US non-denominated alphabet and Make-Up Rate stamps would be valid only for domestic mail, but in fact those stamps are valid on all mail (See USPS IMM 152.2d), so I infer that the rule was dropped at some time.

In the days before stamps, the amount of postage paid for a letter (or the amount due) was often stamped on the face, and even after the use of stamps became common, accounting for the often-complex international rates was written or stamped on envelopes. These rate markings are a popular collecting and study area.

Some recent stamps for domestic mail in Great Britain have no numerals, i.e., no specified rate, but simply a class designation, such as First or Second, and pay whatever rate is in effect for their level of service. They never lose their validity, regardless of changes in the actual rates for those services. In the U.S., on the other hand, the alphabet stamps (see G is for G Stamp) issued to facilitate transitions to new rates, have no numerals, but are issued with a specific value, which remains the same - the "A" stamp is still worth only 15 cents.

The recent semi-postal issues in the U.S., on the other hand, are being treated like the rate class stamps of the UK - they will remain valid for first class postage at the then-current rate. For now, at least.

Click on any image below to view a high-res version

Early uses of numerals on stamps

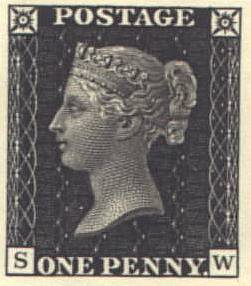

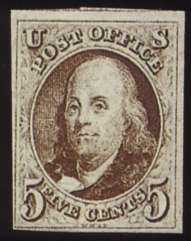

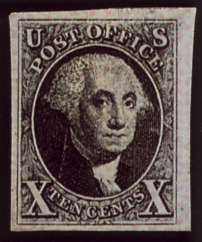

Among the first stamps of Great Britain and the U.S. we have three different proposals for

how to represent the numeral of the denominations. The British chose to spell it out,

while the US couldn't decide whether to use Roman or Arabic numerals. The concept was

new, everyone was experimenting.

In the years since, only two other U.S. stamps I can find (excluding reproductions of

the one above) have used Roman numerals (Scott 728 and 729), and while

some have spelled out the denomination, almost all have had it in Arabic numerals.

UPU Standards for International Mail

Soon after it was established in 1874, the UPU set

standards both for the colors of stamps and the style of numerals to be used on

international mail, so that clerks processing foreign mail would be able to interpret the

rates more easily.

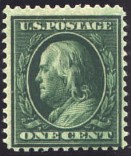

The US had not issued a stamp bearing only a written denomination

since 1869, but for some reason it issued the two at left above in 1908. They

obeyed the UPU rules for colors, but not for numerals, which were required to be

the Arabic style. Granted, neither of these paid a foreign rate, but they

were the workhorses of the series they belonged to, and caused a huge furor.

The stamps were re-issued in 1912 with new, UPU-compliant numerals (the two at

right above), and have continued that way since - numerals only.

Today, UPU regulations no longer stipulate that stamps contain any sort of numerals. Both the volume of mail, and the procedures for exchanging payment for international mail, have changed dramatically. At one time every foreign letter was examined and analyzed, and if the originating Post Office had not caught a shortage in the postage, one along the way was sure to do so. Now it's up to the home country to catch any errors and handle them; once a piece of mail goes abroad, they have to assume the postage is correct, or any amount due is indicated.

Click here to see the current UPU rules about postage stamps on international mail (The highlighting is mine, and the original is far lengthier.)

Click here to visit the UPU web site.

Computer Vended postage

This is one of the odder recent (1992) experiments of the USPS, and aside from stamp collectors, and the patrons of a few post offices in a few areas such as DC and LA, few people even know about it. These stamps could be purchased from vending machines, and their denominations/numerals were printed only at the time of sale. The buyer keyed in the number of stamps and the denomination to be printed. I think they have all been discontinued now, since the machines were very temperamental, and saw little use except by collectors and stamp dealers! On the other hand, similar stamps have been produced by many foreign countries, and seem to be gaining acceptance, especially in Europe, so they could still catch on here, once someone figures out how to market them.

Another recent (1989) experiment in computer-vended postage produced labels like the

ones above. These were issued by a machine that weighed an item, and allowed the

purchaser to specify they type of service desired, then printed and delivered the label.

These too are now just curiosities, though they do look a lot like the labels postal

clerks can print at their counters.

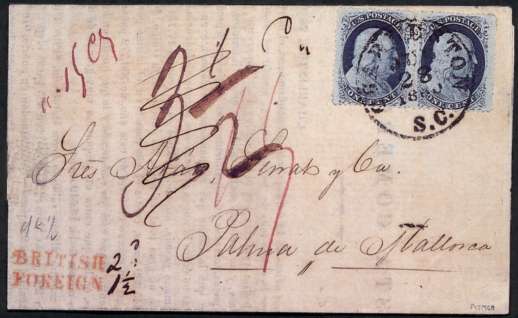

Numerals as Accounting Markings on International Mail, Mid-19th Century

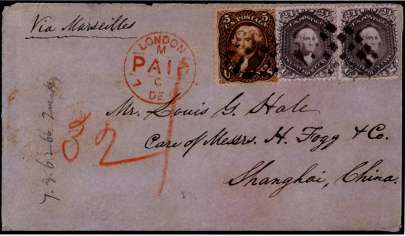

Prior to the formation of the UPU in 1874,

international mails were governed by scores of individual treaties between pairs of

countries, and figuring out the proper rate for prepayment of postage was often mere

guesswork. At each transfer point on its route, the amount of postage paid vs. due for a

letter was tallied and marked on it, using typically black or blue for debits, and red

for credits. Students of postal history enjoy studying covers like the ones above, and

tracing their routes and ratings by the numerals and handstamps on them.

Any experts out there who would care to email me an analysis of any of these covers?

Numerals as Accounting Markings on International Mail, Mid-19th Century (cont)

The auction catalog I scanned this cover from (probably a Siegel auction, pre

3/2000)

described the markings thus:

"...1865 cover to Shanghai, China, NORWALK, [CT] JAN 12 1863 datestamp, red N. YORK BR. PKT. PAID exchange credit handstamp, red London transit, ms. '1' colonial credit, magenta ms. '40' credit, ms. 'via Marseilles', 'INSUFF STAMPED/VIA MARSEILLES' handstamp, Hong Kong and Shanghai backstamps...VERY RARE MULTIPLE FRANKING ON COVER, PAYING THE FORTY-FIVE CENTS RATE BY BRITISH MAIL VIA SOUTHAMPTON, BEING SHORT PAID VIA MARSEILLES, THE COVER WAS CARRIED VIA SOUTHAMPTON, AND TREATED BY THE BRITISH AS FULLY PAID."

Note that this cover (like two of the ones in the prior group) has the desired routing

written on it, in the same ink and handwriting as the address - apparently it was common

for people who sent mail overseas to know what routes were available, designate the route

they wanted the letter to take, and then pay the requisite postage. I know from other

covers that the required postage for the Marseilles route was 53c, but apparently neither

the sender nor the clerk who accepted this letter knew that. The basic rate for postage

within the US was 5c, which leaves 40c for the rest of its journey, and that agrees with

the "40" credit. BR. PKT. presumably stands for "British Packet" (a "packet" is "a boat

that carries mail, passengers and goods regularly on a fixed route"). I've no idea how

common - or rare - it was for postal clerks to override the designated routing for mail

to save having to collect postage due from the addressee, or why the Marseilles route

cost 8c more. But really, what a system!

And here are the covers that told me the rate "Via Marseilles" was 53c. Both are from

about the same date as the previous one, both have the inscription "Via Marseilles, and

both have 53c postage - one even has that very helpful "PAID 53". Yet one has the

manuscript credit "48", which makes sense, it's the difference between 53 and 5; while the

other has a red manuscript "32" - I don't know why.

At this point, either you think anyone who could care about this sort of nonsense is

nuts, or you are starting to wish you knew more, and wonder where one learns about this.

If the latter, I recommend you join the U. S. Philatelic Classics Society, many of whose

members are experts at this sort of thing. The Society publishes a fascinating quarterly

journal - The Chronicle of the U. S. Classic Postal issues, which usually

contains several analyses of covers such as the ones above, explaining the rates and

usages. Link to their web site.

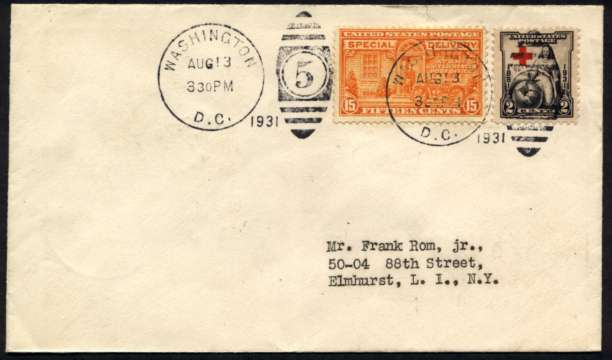

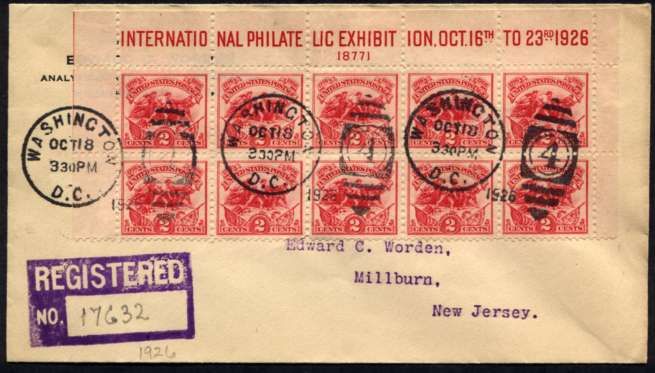

Lozenge Cancellations

The numerals in the lozenge cancellations on these covers identify the clerks who

processed them. Both, incidentally, are First Day Covers for their stamps, and

relatively uncommon, since FDC's did not really catch on until the 1930's. What are they

worth?

The FDC of Scott E16, the 1931 Special Delivery stamp, is valued by Brookman and Scott

at $125. This one is in good condition, so should be worth $100 at retail. The partial

pane of Scott 630 is harder to value. The Scott US Specialized catalog does not value

singles from this sheet, since they cannot be distinguished from singles of Scott 629

(which has a used valuation of $1.70). A full sheet of Scott 630, used, is valued at

$450. What about the First Day cancels? Are they worth anything extra? Well, my 1997

US Specialized values a First Day cover of Scott 630, with the entire sheet, at $1,500.

So is this cover worth 2/5 of that? My 1999 Brookman values a block of 10 with selvage

on a FDC at $250. So I would expect a dealer's price for this to be around $200. I

think I paid about $40 for it, and it was worth that to me.

| Home | M is for Mulready Envelope <<< | Contents | >>> O is for Overprint | Credits |

All text Copyright © 2000, William M. Senkus

Send feedback to the author: CLICK HERE

Revised -- 01/11/2002