R is for RPO - Page 3 |

|

|

|

|

RPO's - How they worked

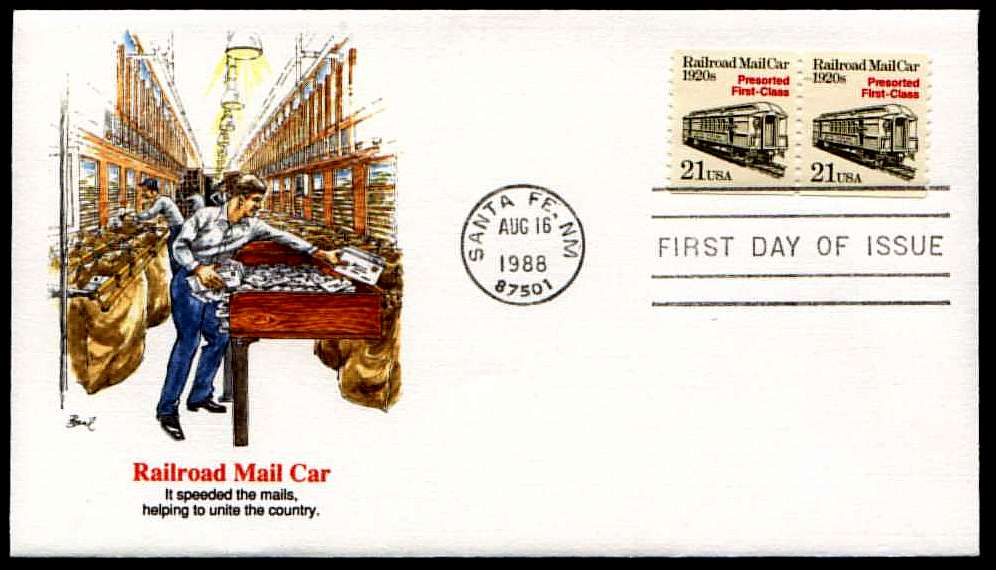

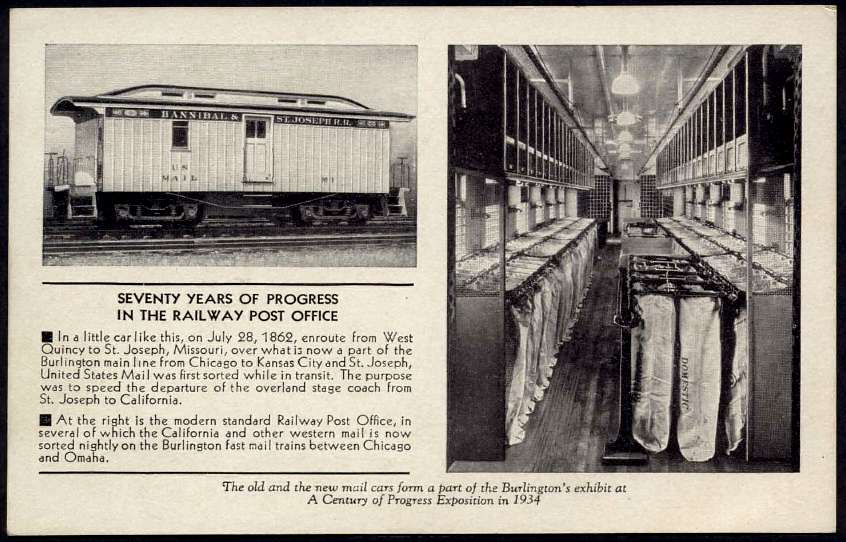

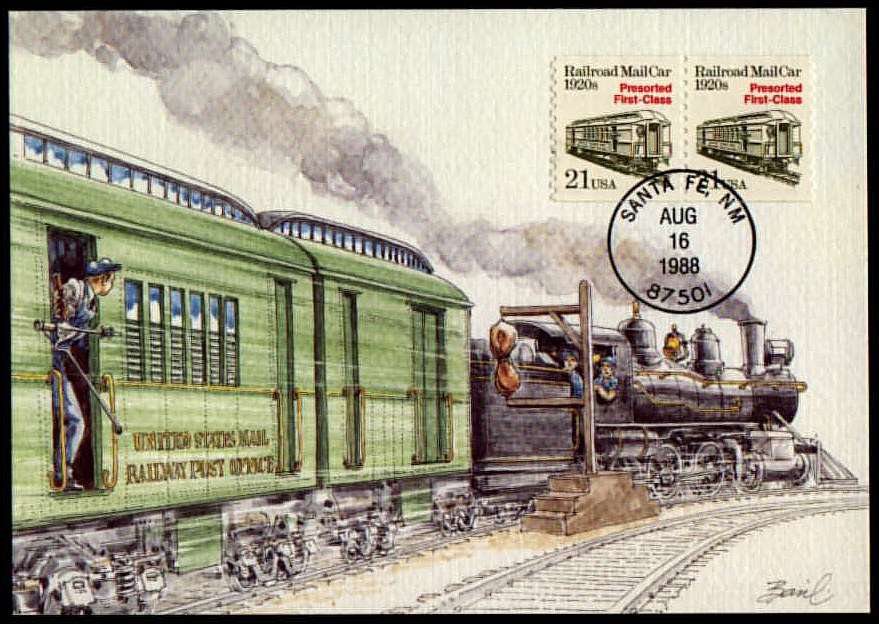

The covers and photos above show the insides of RPO cars, and give a pretty good idea of

how the work was done.

Many aspects of the RMS (Railway mail Service) and RPO's fascinate me. For example, it

was critical to the success of the system that trains not have to stop to drop off and

collect mail bags en route. The dropoff part required no special equipment or skill -

you just throw the bags out! But collecting bags while the train was still in motion

required a special track-side contraption to hold the bag, and an arm that swung out of

the mailcar to snag it. The covers above illustrate the system in use. I suspect the

train still had to slow down.

When the USPS started Air Mail service in 1918, they tried to develop a similar system

for planes, by suspending mail bags high in the air between pairs of poles, but the

planes could not fly slowly enough to snag the bags without either ripping apart the bags

or crashing the plane!

and if a train can do it, why not a plane?

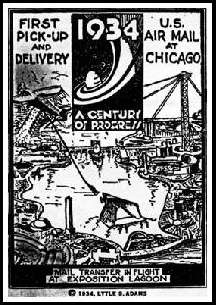

By the 1930's, according to an article by A. N. Glennon in the January, 2000 issue of The American Philatelist, the concept of snagging mailbags on the fly (literally - from an airplane!) had been picked up by inventor Lytle Adams. A popular feature of the 1934 edition of the Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago was the thrice-daily pickup by airplane of bags of mail from the Expo, so apparently the idea worked, given the right combination of equipment and pilot. By 1939, airplane technology had improved enough to make the concept commercially practical -

More about this at the Postal Museum site.Along the way, the airlines tried different ways of moving the mail. One innovative scheme was called ?skyhooking,? which brought the mail to towns that were too small for an airport. In skyhooking, a plane would hook outgoing mail that was hanging on a rope suspended between two posts using a grappling hook on the airplane?s tail. Incoming mail would simply be dropped from the plane?a Stinson Reliant R10. The method required great piloting skill and also reliance on visual landmarks. Begun in May 1939 with a one-year trial, All American Airways Company made 23,000 mail pickups this way along two routes out of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and won a contract to continue the service for 10 years. By the summer of 1941, the line was serving more than 100 locations and picking up some 400,000 pieces of mail each month. However, All American could not get the Civil Aeronautics Board to extend the service to other regions of the country. The airline dropped its pickup operations in 1949 and converted to carrying passengers.

from http://www.1903to2003.gov/essay/Government_Role/1930-airmail/POL6.htm

I own some First Flight covers from that era that illustrate the system - click here to open a page that shows them.

Like the Zeppelins of the same era, this is to me an amusing and interesting byway of technology, an idea that lived briefly only because of its inventor's obsession and persuasiveness. In retrospect we can only ask "What were they thinking?"

Click here to access my web page on Poster Stamps of the 1933

Century of Progress Expo in Chicago.

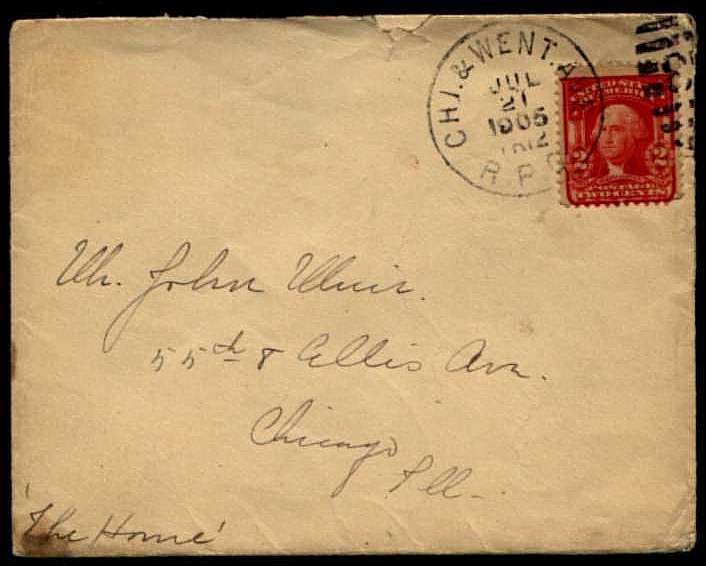

Streetcar RPO's

There were even "Streetcar RPO's", which were common in large cities from the 1890's

through the 1920's. Mail could be deposited through slots in the sides of special postal

streetcars, and was postmarked, sorted, and dropped off as the vehicle travelled its route.

Keep in mind that this was in the days when the USPOD offered two or even three

deliveries per day in cities. One could mail an invitation to a party in the

morning, and receive replies by the end of the day, for a party that night!

So a streetcar functioned within a city much as a train functioned on its

much longer route, continually collecting and delivering as it went.

The cover above was postmarked on Chicago's Chicago and Wentworth Avenue line in 1905.

How to Collect Them

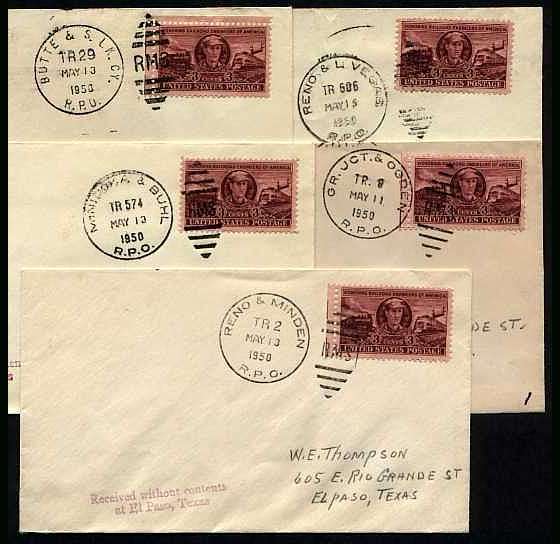

If you've been reading these pages in sequence, you may remember the cover at the bottom

of the group shown here. I showed it on the "H" page, where I

noted that I suspected it had been created by an RPO collector. These covers are the

reason I made that statement - five of them, all addressed in the same hand and to the

same person, all empty, and all postmarked within a day or two of one another. They are

souvenir covers created by a collector to obtain the RPO cancels. The goal is to obtain

a sample usage of every possible RPO cancel for a railroad or route, which was hard

enough in the early days, but a formidable challenge in this century, unless one aided

the process like this. Did the collector drive to each of the origins and post the

envelopes himself, or mail them to the local post offices to be returned to him?

Perhaps he was on a summer vacation, and mailed them along the way. And in case you

are wondering, three of these five ended up with the "Received without contents"

handstamp.

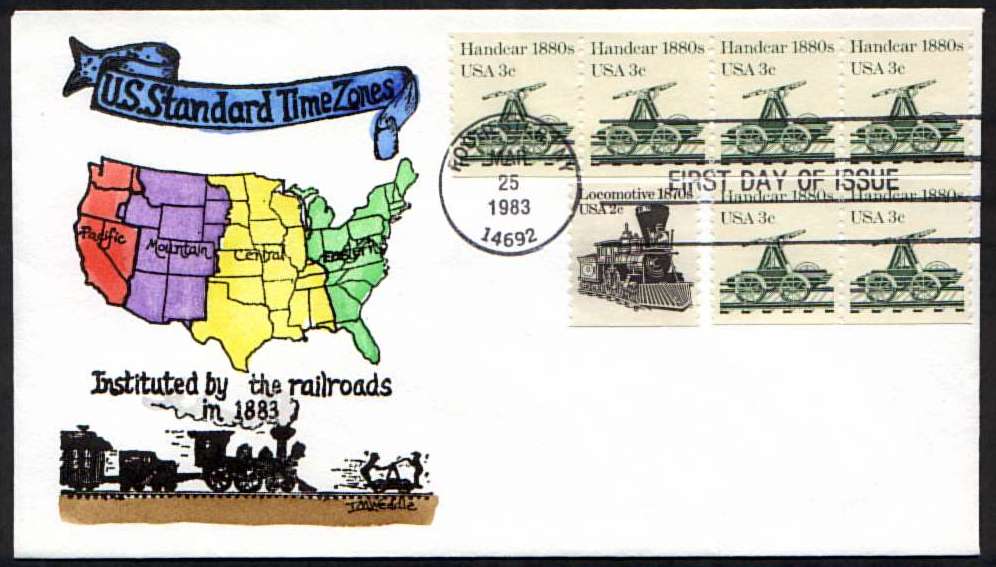

How the Railroads Created Our Time Zones

The cover above is a favorite of mine not for its artistic merit or scarcity - its design is simple, it was mass- produced, and I bought it for a dollar or two, for its stamps and First Day cancel, hardly noticing its cachet. When I finally did look at the cachet, it gave me a start - Could it be that our modern Time Zones had not always existed? What did trains have to do with them? Will Luke marry Laura? Read on for the full story.

Here in the U.S., amateur astronomer William Lambert unsuccessfully lobbied Congress to establish standard time meridians as early as 1809, and for most of the rest of the 19th century there was no standard time in the US. All the cities and villages throughout the United States - indeed, throughout most of the world - were on 'sun time'. Clocks were set at 12:00 noon when the sun was directly overhead, but this time changed from city to city. When it was 12:00 noon in Washington, it was 12:07 in Philadelphia, 11:53 in Buffalo, 12:12 in New York and 12:24 in Boston. To make matters worse, each railroad chose its own time. Trains pulling into the Pittsburgh terminal had their clocks set to six different times. In all, American railroads operated on more than sixty different times.

Railroad companies soon found that to operate efficiently, trains had to arrive and depart on time, which meant that locomotives had to be readied on time, trains had to be made up on time, baggage and mail had to be loaded on time, track repairs had to be finished on time, and train crews and station agents (not to mention passengers!) had to report on time - all of which was difficult with such a chaos of clocks.

Great Britain was the first country to recognize the benefits of standardized time-keeping, The precedent was set there as early as 1840, when the Great Western Railway established nationwide "railway time" in the fall of that year. By 1855 the vast majority of public clocks in Britain were set to Greenwich Mean Time, though some, like the great clock on Tom Tower at Christ Church, Oxford, were fitted with two minute hands, one for local time and one for GMT. The last major holdout was the legal system, which stubbornly stuck to local time for many years, leading to oddities like polls opening at 08:13 and closing at 16:13. The legal system finally switched to GMT when the Statutes (Definition of Time) Act took effect - it received the Royal Assent on August, 2, 1880.

Standard time in the US was largely the creation of two men - educator Professor Charles F. Dowd, and railroad engineer William F. Allen, secretary of the American Railroad Association. Dowd developed and promoted the idea, while Allen championed it among the railroads. It took them 13 years, but in 1883 their efforts finally paid off - the United States was divided by the railroads into four time zones. With that change it became possible to publish accurate schedules, and with trains running on standard time many accidents were avoided.

Sandford Fleming of Canada is often credited as the "inventor" of Standard Time, as he was a key promoter and organizer of the extension of the idea world-wide. It was at Fleming's instigation that twenty-six countries sent delegates to Washington in 1884 to discuss the "Time Reform Movement". Standard Time was soon extended to the rest of the globe, though well into the twentieth century many areas continued to buck the trend - Detroit, for example, kept local time until 1900 when the City Council decreed that clocks should be put back twenty-eight minutes to Central Standard Time. Half the city obeyed, half refused. After considerable debate, the decision was rescinded and the city reverted to Sun Time! A derisive offer to erect a sundial in front of the city hall was referred to the Committee on Sewers. Finally, in 1905, Central time was adopted in Detroit by city vote.

And though it had been accepted almost universally by then, Standard time was not established in U.S. law until the Standard Time Act of 1918!

References:

The Spectacular Trains, A History of Rail Transportation, John Everds, 1973, Hubbard Press

http://webexhibits.org/daylightsaving/d.html

http://www.mackinac.org/article.aspx?ID=4423

( Want to know more about this fascinating topic?)

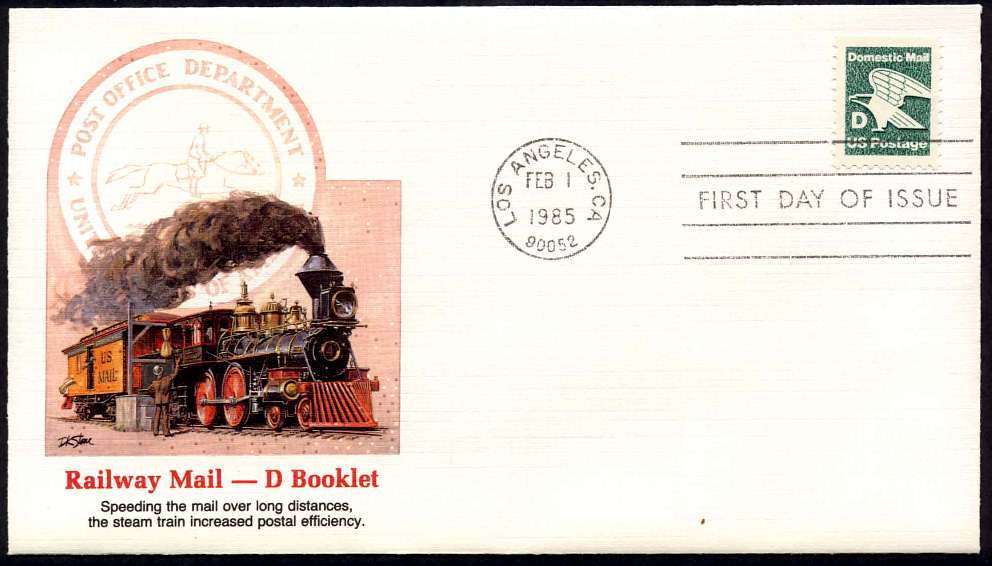

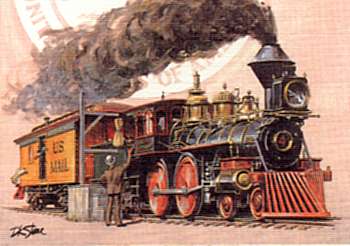

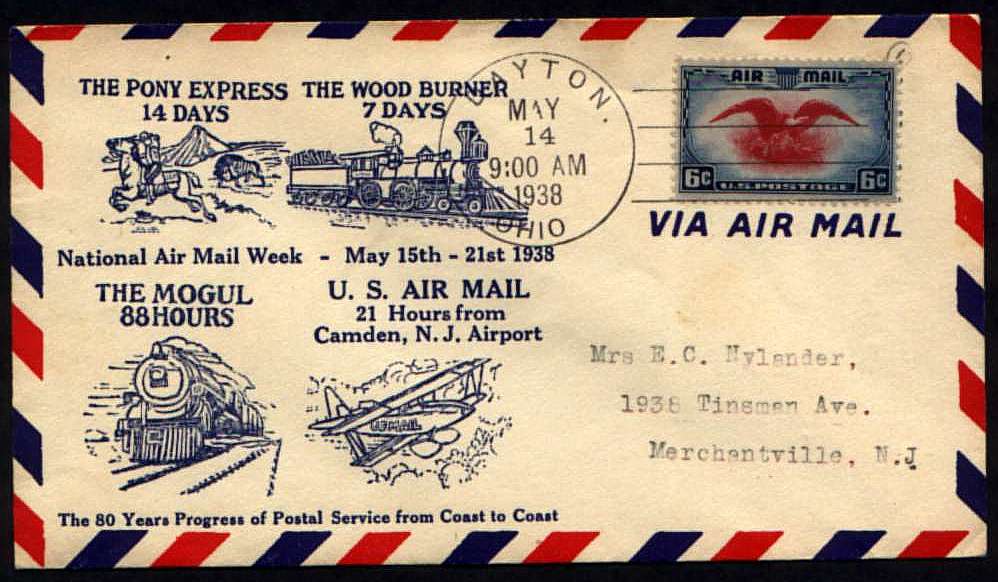

The History of Mail Transport to 1938

I like any cover with a picture of a train on it, and if it educates me a little as well, so much the better. This cover also happens to be a First Day Cover for its stamp, which enhances the value a little.The text at the bottom of the cover says "The 80 Years Progress of Postal Service from Coast to Coast", and above are illustrated four milestones, from 14 days by Pony Express in 1860, to 21 hours in 1938 - not quite 80 years. If we consider a real 80-year span, the Coast-to-Coast time was probably at least a week longer before the Pony Express, but I agree this selection of highlights is more romantic than strict accuracy would be.

By the way, Did you know that the Pony Express lasted for only 19 months, from April of 1860 to October of 1861? It was put out of business by the completion of the first trans-continental telegraph line. For more about the development of Air Mail, see F is for First Flights.

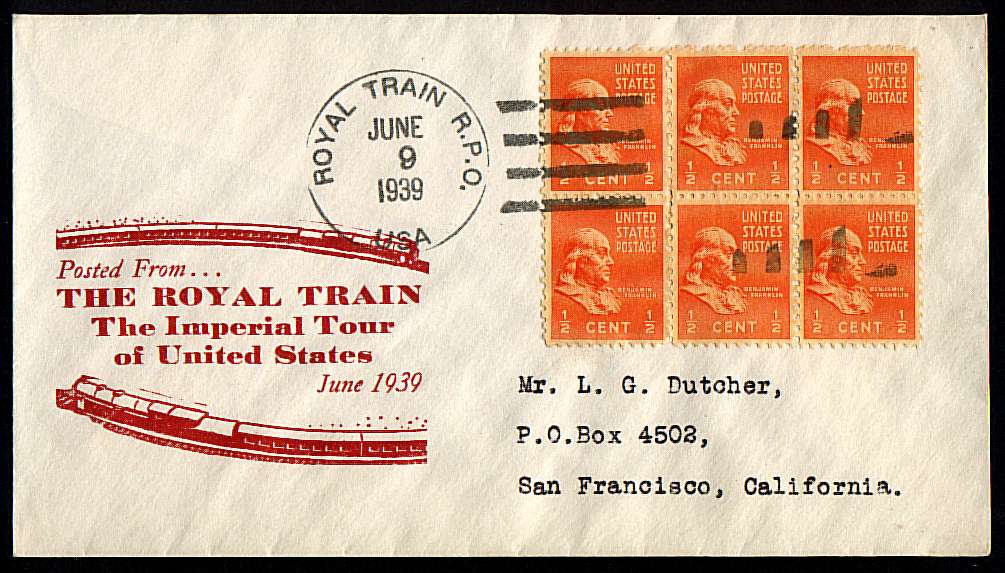

The Royal Train!

I don't share the popular love of royalty, so to me these are just an amusing curiosity. The British royal family toured North America in 1939, riding in a special train. There were souvenirs by the thousands, of course, including covers like these, cancelled on the train's "RPO". I put quotes around it that way because its purpose was not to carry mail, but to create souvenirs.

Home R - page 2 <<< Contents >>> R - Page 4 Credits

All Letter images Copyright © 1997, 2000, SF chapter of AIGA

All text Copyright © 2000, William M. Senkus

Send feedback to the webmaster: CLICK HERE

Revised -- 1/18/2007