PARCEL POST STAMPS - 1912, 1913

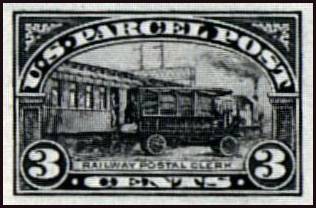

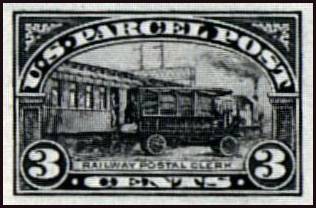

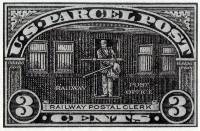

Sc. Q3 - issued 4/5/13

Postal Clerk

in door of railway post office car

|

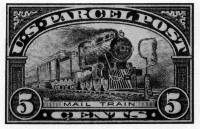

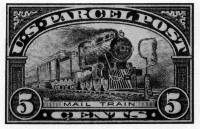

Sc. Q5 - issued 11/27/12

Steam locomotive, mail & passenger car

approaching mail pouch pickup

|

Sc. Q9 - issued 11/27/12

Private business car & freight cars

at steel plant, Chicago, Ill.

|

Henry M. Gobie, in his excellent book U.S. Parcel Post, A Postal History (published by the author's wife in

1979), refers

to the Parcel Post stamps as "the Fourth Class Follies of 1913." They are among the shortest-lived of U.S. stamps,

with an

official usage period of only six months, January through June, 1913. During that period, all parcel post had to be

franked with

these special stamps, and they could be used only for parcel post. Below are all twelve denominations of the series,

1¢

through $l. The vignettes are attractive and well-executed, including the first airplane on any postage stamp of

the world,

and three train scenes, paying tribute to the prime role trains still played in moving the nation's mail at that time.

The main opponents of the new stamps were postal employees, for many reasons: their size - too large to

fit them

where they needed to go, such as on parcel tags; their color - all the same, so it was difficult to tell

them

apart; the number per sheet - 45, an awkward number; and their very existence - no clerk

needed a

whole new set of stamps to keep track of in addition to all the others in his drawer.

Reason prevailed - after July 1, 1913, there were no restrictions on either what stamps should be used on parcel post,

or what

sort of mail could be franked with parcel post, and stocks were allowed to run out through ordinary use.

In his very useful book, "Standard Handbook of Stamp Collecting",

Richard McP. Cabeen, who was

editor of the stamp-collecting column in the Chicago Tribune for 37 years, 1932-1969,

gave a different explanation of the purpose of these stamps, and why they were discontinued, as follows:

After years of debate the United States issued parcel post stamps late in 1912 to check the receipts from this new

service. It was quickly determined that the service was self-supporting and June 26, 1913, an order discontinued the

stamps and made existing stocks valid for the payment of any postage.

That certainly makes sense, but begs the question Why does everyone else say the whole affair was just

bureaucratic nonsense?

According to Gobie, the BEP Record Cards for the three rail-themed stamps read as follows:

- for the 3¢ - "From photo taken of a P.O. Railway Train, submitted by the Post Office Department."

- for the 5¢ - "From photo of train at Union Station, Wash., D.C."

- for the 25¢ - "From photo of an Illinois Factory submitted by the Post Office Dept."

Gobie adds some interesting background about the 3¢ stamp:

In his column in "STAMPS" of June 3, 1933, Sloane said of the design:

"Incidently, the car which is pictured on the stamp was drawn

from a photograph, which I saw some years ago, of a railway mail car of

the Baltimore & Ohio R.R., the mail clerk standing In the doorway. In

the stamp design, the lettering at the top of the car is omitted, but the

clerk joins those selected few, who, living, have had their likeness

appear on the postage stamps of the United States."

Further comment from Sloane appeared in "STAMPS" of July 3, 1954;

"The view of the postal clerk shown on the 3¢ Parcel Post

stamp of 1913 as standing in the open door of a railway mall car was

engraced from a photograph which was later reproduced on the front

cover of 'The Postmasters Advocate', August, 1915 issue. The car shown

on the stamp carries no identification of a railroad but the picture

mentioned showed the words, "& OHIO" across the top of the car -

undoubtedly a Baltimore & Ohio car (with very remote possibility

Chesapeake & Ohio R.R.) The photograph was posed and probably was

made from a loading platform in the Union Station, Washington, D.C. To

my view, a much more interesting picture appeared on an essay for this

stamp which was not adopted. This showed a mail truck backed up to

the mail car of a waiting train, the locomotive up front puffing steam."

Johl evidently located some reference to this change in design:

"This delay was due to the disapproval of the first sketch for

this denomination, a section of a mail train at a station platform, a

'Railway Postal Clerk' standing in the door of the last car ready to

receive some bags from a truck backed against the car. The Postmaster

General felt that too much prominence was given to the truck and not

enough to the Postal Clerk, the result being that the design did not tie

in with the other lower values depicting 'working personnel.'

A new design was made showing clerk standing in the door of a mail

car, holding a bag of mail attached to an iron arm preparatory to

swinging it out to be picked up by an automatic mail receiver at the next

station. In this stamp the 'personnel' Is accentuated instead of a method

of collection or distribution, and as such was thought to be more

appropriate as part of the first group."

Here's how that rejected design looked, and the final design (both reproduced from Gobie's book):

The locomotive on the 5¢ stamp looks like either an 0-8-0 or an 0-8-2 (unlikely) of the period,

with enough detail that a fairly close identification should be possible, especialy given the location (Union Station),

which would limit the railroads it could have belonged to.

The artist obviously added the mail pouch post and smoke to the 5¢ stamp to simulate the train's motion.

Below are two of the essays produced on the way to the final design (from Johl), and the final

design (from Gobie).

The first was rejected because the mail bag pickup device was too inconspicuous.

The second is much closer to the final design, but the mail pickup rack was an old

style, replaced with a more modern one on the actual stamp.

Of the 25¢ stamp, Max Johl (in his United States Postage Stamps of the 20th

Century), writes that "the vignette was based on a photograph of a steel plant

in South Chicago. It was supplied by J. E. Ralph, then Director of the Bureau

of Engraving and Printing, and it is claimed that at one time he had been an

employee of this mill." Below (from Johl) are two essays with early versions

of this vignette, and the final design.

Note that the denominations on the essays are different - the decisions about

which design should go on which stamp went through several revisions.

Most sources I consulted describe the rail car in the foreground

as a passenger car, but looking at the configuration of its windows, and considering where

it is - the rail yard of a steel plant - I think it is a private business car.

Over 100 million copies of the 5¢ stamp were issued, so it should be relatively plentiful, but a decent

unused copy will cost you about $25, so most must have been used, rather than saved. By contrast, the

3¢ stamp, of which only 29 million were issued, retails for about $10, while the 25¢ stamp,

with 22 million issued, sells for $60.

Since the stamps were not valid on ordinary mail until July 1, that is regarded as their First Day,

and covers with that date are treated as FDC's, which are known to exist for the 1¢, 2¢,

3¢, 4¢, 5¢, and 15¢ values, and fetch high prices. Valid ordinary covers

dated in the nineteen-teens are not common, and often are priced higher than mint copies of the stamps.

Dated postal uses before July 1 are entirely philatelic, but still valuable.

Legitimate uses on parcels before 7/1/13 are usually undated, unless the parcel was sent with some

additional service such as special delivery, so any dated use in that period is also potentially valuable.

|

The

Shreves Auction Galleries sale #53 of October 18-19, 2002 included an extensive selection of

parcel post usages, three of which are shown below with their auction catalog descriptions.

|

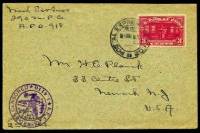

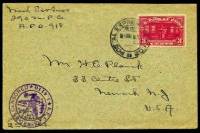

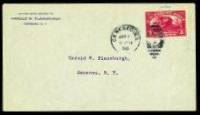

LOT 970:

#Q3, 3c Parcel Post, well centered, tied to fresh cover to Newark, N.J. by

"Postal Express Service/5 Mai./No. 918" American Expeditionary

Forces c.d.s., purple A.E.F. violet censor handstamp at bottom left, an

extremely fine and most unusual usage; illustrated on page 93 of

U.S. Parcel Post - A Postal History, by Henry M. Gobie; ex-Doolittle.

Est. 300-400, SOLD for $1,150.00

|

LOT 962:

#Q5, 5c Parcel Post, a single example with deep luxuriant color tied to neat cover by "Genesco, N.Y./Jan 1/1913"

duplex cancel,

being an

enormously rare first day cover (the first day the stamps were available), "Harold W. Flansburgh/Genesco, N.Y." corner

card and

addressed to

himself, very fine; one of the most important Parcel Post first day cover rarities known, as this is the only recorded

(non-

combination)

Five Cent value used on January 1, 1913, the very first day the Parcel Post stamps were available to the public; one

of the

highlights of

the Bothamley collection; ex-Doolittle.

Est. 5,000-7,500, SOLD for $10,500.00

|

LOT 982:

#Q9, 25c Parcel Post, natural s.e. at top, tied to cover to Bergen, Norway by "Hillsboro, N. Mex./Jul 19/1913" duplex

cancel,

Bergen bkst.,

cover with small edge tear at left, fine; a very scarce usage of this value; ex-Doolittle.

Est. 200-300, SOLD for $250.00

|

THE COMPLETE SET

Here is how the official USPOD release described them:

|

1¢ - "Post Office Clerk." This view shows a distributing section of the Washington, D. C. , post office.

2¢ - "City Carrier." The design shows a mail carrier at the door of a residence.

3¢ - "Railway Postal Clerk." He stands at the door of a mail car removing a sack of mail from the sack catcher.

(The

first design,

which was not used, showed a Parcel Post automobile driver transferring mail through the door of a railway mail car

with the

assistance of

the railway postal clerk.) 4¢ - "Rural Carrier." The design was made from a model mail wagon in the Post Office

department at

Washington. A horse was hitched to this wagon and a photograph taken of the outfit. The engravers supplied the

background of

foliage.

5¢ - "Mail Train." This is an "action photograph." It is a design which gives a semblance of speed to the train

which is

shown

approaching a suspended mail bag.

10¢ - "Steamship and Mail Tender." The design is a reproduction of a photograph of the Kronprinz Wilhelm in

New York

harbor.

Staten Island is covered with skyscrapers in the design which has been criticised as being geographically

incorrect.

The effect is

good in spite of the critics' thrusts. The mail tender was added to the design to show the relative size of the

liner.

15¢ -

"Automobile Service." A postal employee is approaching an automobile. Substation "A" and a residence across the

street form the

background. 20¢ - "Aeroplane Carrying Mail." A biplane in mid air carries the navigator and a sack of mail.

(The first

design,

which was not used, showed no mail sack.)

25¢ - "Manufacturing." The design shows a part of a steel plant in South Chicago. It is said that the

original of this

design is a

photograph supplied by Director Ralph who was at one time employed in the plant. 50¢ - "Dairying." Two

designs were

prepared for

this stamp, which shows some cows grazing in the foreground and a group of farm buildings in the distance. The original

photograph was

supplied by the Department of Agriculture. In the finished design which was approved the buildings are less prominent

than in

the original

essay.

75¢ - "Harvesting." The photograph supplied by the Department of Agriculture shows a thrashing machine,

teams and men,

and a

prominent straw stack; much of the scene was faithfully reproduced by the engraver. $1.00 - "Fruit Growing."

Several

proofs, differing

in minor details, were prepared for this stamp. The issued stamp shows a group of workers in an orchard.

|

So were these stamps indeed a folly?

Perhaps so. What must not be overlooked, however, is

what they symbolize, namely a revolutionary change in USPOD policies and a profound change in American business - the

creation of

our first Parcel Post system. Prior to January 1, 1913, the USPOD would not carry parcels weighing more than 4

pounds, and

there were

severe restrictions on what could be mailed. After January 1, 1913, the weight limit was raised, first to 11 pounds,

then to

20, then to

50. AND there were almost no restrictions on what could be mailed. The result was a flood of mail that many feel

changed the

country

forever. It was in fact the last step in a change that had been taking place for several decades, notably with the

initiation

of Rural Free

Delivery in 1896. If this topic interests you, I recommend Reaching Rural America: the Evolution of Rural Free

Delivery,

by James H.

and Donald J. Bruns. James Bruns is the former Director of the National Postal Museum, and a prolific and entertaining

author on

postal history.

|