|

<<<< |

|

>>>> |

|

TRAINS ON U. S. STAMPS

and POSTAL STATIONERY

page 2c

Embossed postcard with train image - Limited Express |

2-cent Panama-Pacific Issue - Jan. 18, 1913 and Jan. 1915

| ||

Scott 398, Jan 18, 1913 - 2 carmine, perf 12 Scott 402, Jan, 1915 - 2 carmine, perf 10 |

The Panama Canal was one of the greatest engineering achievements of all time, not only for its size, but also for its impact. Some would say it has never been equaled, though a strong candidate today would have to be China's notorious Three Gorges Dam.

The Canal opened on August 15, 1914, shortening the ocean trip between New York and San Francisco by almost 8,000 miles, and changing the world of its day. It still plays a critical role in international commerce. Many ships today are built specifically to fit the Canal - they are called the "Panmax Class," because their length, width, and draught are the maximum the Canal can handle.

Scott 398 was issued January 18, 1913, one of the four commemorative stamps issued to promote the Panama-Pacific Expo in San Francisco, Feb 20 thru Dec 14, 1915. The Panama-Pacific Expo had two purposes - to celebrate the opening of the Canal, and to celebrate the resurrection of San Francisco from the devastation of the 1906 quake. The stamp depicts the Pedro Miguel locks of the Canal, with two ships passing through. Its design remained in service for an unusual three years. When the BEP changed its standard perforation from 12 to 10 in late 1914, subsequent printings of the stamp received the new perforation, creating Scott 402.

The USPS publicity for the stamp described it thus:

The 2-cent stamp is carmine. It represents the Panama Canal, with a merchant steamer emerging from one lock and a warship in the other. The mountains of the Isthmus appear in the distance, and palm trees on the right-hand side of the locks. Beneath the picture are the words "Panama Canal."

Such eloquence.

An astonishing 502 million of Scott 398 and 402 combined were issued, yet mint hinged copies of the two stamps catalog $21 and $75, respectively, reflecting both their age and their popularity at the time. The designer was C.A. Huston, and the engravers were M.W. Baldwin (vignette) and E.M. Hall (frame). There are some minor color varieties, and various minor plate varieties, but no known errors.

Nice covers with the Panama-Pacific stamps are surprisingly hard to find. FDC's are even more so. The cover above, with all four stamps of the 1913 issue, is not a FDC - there could not be such a cover with all four stamps, since 398 was issued separately - but this one is relatively early, and while obviously philatelic, is attractive and appealing. By my calculations it is overfranked by six cents, unless it was much heavier than it looks. First Class postage was 2¢ per ounce at the time, and Special Delivery was 10¢, so 12¢ would have done the job.

So what's the rail connection?

In the ATA Handbook World Railways Philatelic there is the following caveat above the listing for U.S.A. Scott 398 and 402:

Note: Some collectors consider the railway interest of the two following stamps as speculative.

Why?

Anyone who knows how the locks of the Canal work would expect to see at least one pair of "mules" per ship in the image. (Mules are the small electric rack-and-pinion railway engines that pull all larger vessels through the locks.) Two pairs of mules are the rule for all but the smallest vessels, and large ships have required as many as six pairs. Close examination of the image reveals no trace of the mules, though, nor of the tracks they run on. Moreover, the image is surprisingly crude, with ships that look like a child's toys, not real ocean-going vessels

One tipoff that this stamp was odd was its date of issue - the other three stamps of the set had been issued on January 1, but this one was not issued until January 18. Why was this one delayed? And why no "mules"?

The answer is an amusing tale that illustrates the old saying: "There's many a slip twixt the cup and the lip."

The full story is revealed in Max Johl's indispensable The Unites States Commemorative Stamps of the 20th Century.

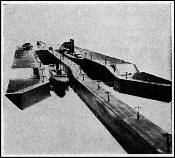

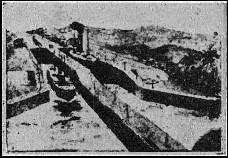

At the time the Panama Canal stamp was being designed, its subject was two years short of completion, and the only photographs available were not adequate as source images. The Director of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing knew that there was a model of the Canal's locks on display at the War Department a few blocks away, and arranged to have the model filled with water. Model ships were then floated in the display, and a photograph of the result was taken. At left below is that photo, as reproduced in Johl's book:

A BEP artist used that photograph and ones from the site to create the painting at right above (also from Johl's book) for the engraver to work from. The photo of the model actually shows what may have been intended to represent the tracks for the mules, but the painter dropped those, and eliminated most of the scant details on the model ships. The result is almost cartoon-like in its simplification and stylization, and there is no hint of either rails or mules, period.

Moreover, somewhere along the way someone thought the locks pictured were the Gatun Locks, so that was the caption on the initial printing of the stamps! Fortunately, they found out it was really supposed to be the Pedro Miguel Locks before the stamp was issued. The entire initial printing of over 30 million stamps was destroyed, the caption was changed to just "Panama Canal" (once burned, twice wary), and the stamp was reprinted.

Even the USPS publicity for the stamp admitted the mixup:

A model of the Pedro Miguel Locks was used as the subject of the 2-cent denomination. The title was first erroneously engraved "Gatun Locks" but the mistake was discovered before any of the stamps were issued, and all of those which had been printed were destroyed by burning. The title was reengraved as "Panama Canal," and the stamps were issued with that title.

If anyone thinks the mules are really there, just too small to see, consider the photo below, of the first ship traversing the Canal on its official opening day. It was the Ancon, a private passenger ship. The photo was the source image for Scott 3183f, on the Celebrate the Century pane for the 1910's.

The mules are small, but hardly so small they would not be visible in the image on Scott 398/402. The artist just didn't know they should be there. Most likely, no one involved in the design process did.

So, while one can call this a rail-related stamp (perhaps in the same spirit as calling stamps that depict the modern SF-Oakland Bay Bridge a rail stamp because the bridge once carried rail traffic), there are no mules there, and no rails there, hence to me this is not a rail stamp, period.

11/24/05 - In response to my comment above about the Bay Bridge, Horst Brix, a member of the Casey Jones Rail Road Unit of the ATA of the USA, and of the Motivgruppe Ingenieurbauten and Internationale Motivgruppe Eisenbahnwesen, both of Germany, wrote as follows:

You are wrong to say that the SF-Oakland Bay Bridge is no longer a rail bridge, simply because it carries no rail traffic.

A railway bridge is built completely differently than a road bridge. The Bay bridge had three rail tracks in the lower floor, two of them for the trolley traffic and one for the big trains. From an engineering point of view, a rail bridge needs additional building elements than a road bridge, because the statics of such a bridge are quite different. The vibration created by a big goods train or a high speed train are much greater than those of cars and trucks running over the bridge. You can always use a railway bridge as a pure road bridge, but you can never use a bridge built as road bridge to carry big trains, unless you upgrade or rebuild the bridge to handle the added stresses. For this reason a railway bridge is from an engineering view always a railway bridge. I have confirmed this with the bridge engineers of the "Motivgruppe Ingenieurbauten".

My thanks to Horst, for setting me straight on that.

References:

The Unites States Commemorative Stamps of the 20th Century, Max G. Johl, pub. H. L. Lindquist, NYC, 1947

Encyclopedia of Plate Varieties on U.S. Bureau-Printed Postage Stamps, published in 1979 by the BIA

United States Postage Stamps, Stamps Division, USPS, 1982

If the Panama Canal holds any interest for you at all, spend some time surfing the Internet for sites about it. There are scores of sites devoted exclusively to the topic, many excellent, with fascinating text and amazing images.

And if you want to read about a truly astonishing alternative to the Canal that was proposed by the famous engineer James B. Eads, go here: http://www.catskillarchive.com/rrextra/pcsa1.Html. Eads proposed the most grandiose scheme of his career, a huge railroad to transport ships above-ground across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, in Mexico!

US TRAINS

|

Send feedback to the webmaster: CLICK HERE

Revised -- 11/24/2005