O is for Overfrank |

|

|

|

|

Is Overfranking a philatelic sin?

In the first incarnation of this philatelic alphabet as simply a slide show created to inform and entertain non-collectors, we didn't worry about adhering to a strictly philatelic vocabulary or set of themes. So while few serious stamp collectors would recognize the term "Overfrank," we didn't let that prevent us from using it, if only for the material (and humor) it allowed us to include. But as I hope to show on this page, it is a topic worth pursuing.

First, what does "Overfrank" mean? Well, the verb "frank" means (according to my dictionary) "to mark (a letter, package, etc.) for transmission free of the usual charge, by virtue of official or special privilege." Presidents, members of Congress, Postmasters, and other government officials have long had this authority - their signature serves in place of a stamp to prepay their official mail, so one says they have the "franking privilege."

Based on that definition, the term "frank" has come to mean "prepay postage." So to apply a stamp to an envelope is to frank it.

"Overfrank", then, means to use more postage than necessary, and while No, it is not a

sin, it can create interesting challenges for the postal historian, to whom it is often

important to understand why a particular amount of postage was used.

NOT Overfranked

Let's start with an item that is NOT overfranked, because that illustrates one of the reasons the question is important - it teaches us about postal rates and procedures. The envelope above contained advertising mail, and was part of a mailing that probably numbered in the millions of pieces. Its stamp has no denomination at all, because the exact amount paid was based on a complex formula involving the total number of items, and/or their total weight, and/or how far they were being sent, and/or the phase of the moon, etc. The postal service likes stamps like this because new ones do not have to be issued when rates change - the stamp is almost incidental to the actual payment of postage. Indeed, the sender could have skipped the stamp entirely, and simply printed a box with words like "Permit" or "prepaid" in its place, but marketing studies have shown that mail with stamps is much more likely to be opened, so businesses use stamps, even when they cost a little more.

On the other hand, businesses do NOT want to overfrank - when you mail thousands of items a DAY, even a tiny increase in cost can make a big difference on the bottom line, so large businesses are careful to use only as much postage as needed, and to take advantage of all the special rates for bulk mailing. Hence, you can be sure that this item is not overfranked.

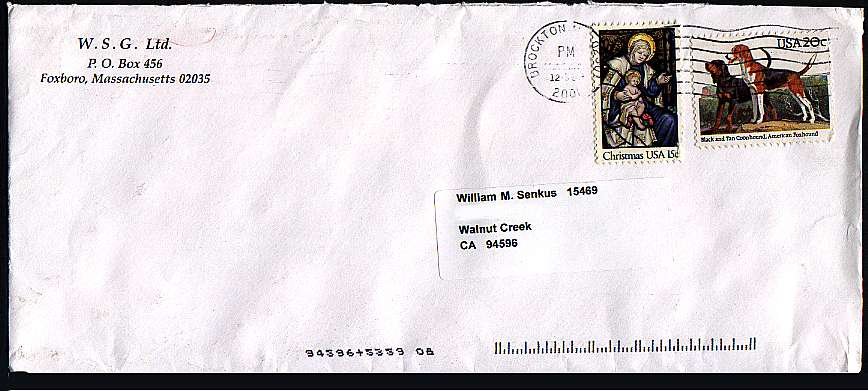

Your Basic Overfranking

Above are two good examples of basic overfranking. The first-class rate for a standard- size, under one ounce letter was 34¢ when the item on the left, containing a price list from a stamp dealer, was mailed, and it qualified for that rate, but it had 35¢ postage, a one-cent overfranking. The dealer was using up old postage obtained at a discount, and felt it was cheaper to waste a penny than take the time to make up the rate exactly. In this case the number of letters the dealer sends per day is not large enough to make a difference.

The item on the right, from a friend, qualifed for the basic 32¢ first-class rate, but has twice that amount. The sender was probably unsure whether it weighed more than an ounce, and wasn't sure what the rate for a second ounce was, so slapped on the extra 32¢ stamp to be sure. I do this sort of thing myself - it's just cheaper to use too much postage sometimes, rather than make a special trip to the Post Office to find out the correct rate.

Note, however, that an item that is square (or nearly so) may be subject to a special "nonmachinable mail surcharge," currently (7/11/13) 20¢, because it confuses the machines that sort and cancel letters. The machines cannot tell which corner should have the stamp. So the item requires human intervention, and that costs extra. The rule is that if an item weighs one ounce or less, and the ratio of its width to its height is less than 1.3 (or greater than 2.5), the surcharge applies. So my friend may have thought her item fell into the almost-square category. I've measured, though, and the ratio of its length to its width is 1.35, hence one stamp would have been enough.

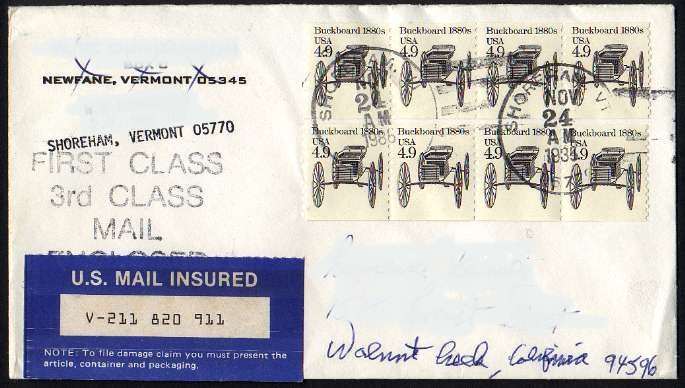

Problem #1

OK, then what about this one - mailed on 11/24/86, it has a total of $1.62 in postage -

is it overfranked?

This is the sort of postal history question I mentioned at the

beginning - How do we know whether there's too much postage or not?

The item looks like it was sent by a stamp dealer, so maybe he too chose to use a little more than

necessary.

To answer the question we need to know the first class rates and the Postal Insurance

rates on the day it was mailed. Not long ago it could have taken a lot of work to

unearth that data, but the publication in 1993 of

"The Beecher Book" (revised edition published in 1999)

made it a one-stop task. The rates were as follows:

1st ounce, first-class = 22¢

Addl oz, first-class = 17¢

Insurance - $25.01 to $50 = $1.10

Insurance - $50.01 to $100 = $1.40

So if we assume the letter was under one ounce, and insured for a value of $50.01 to

$100, the total postage required would have been 22¢ + $1.40 = $1.62. I conclude

the letter was not overfranked.

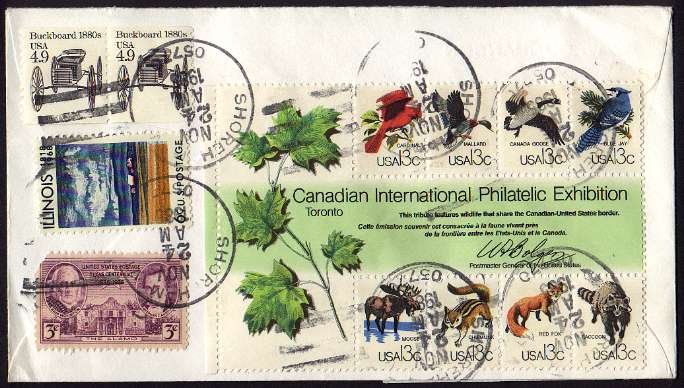

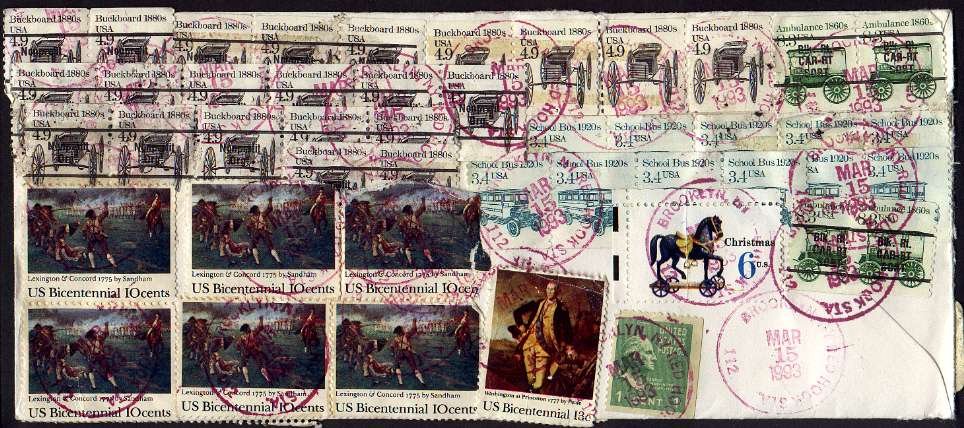

Problem #2

What about the item above? This holds the record in my experience for largest number of stamps used on one envelope. Almost every available square millimeter of space is covered, back as well as front, and on top of that the stamps are heavily overlapped, a violation of postal regulations - how do we know some of the stamps had not been used before, and the overlapping covers their cancellations? So either the sender applied the stamps under the watchful eye of a postal clerk, or he had won the trust of his local postal employees, and they simply accepted the item. In either case, WHEW! Can you count the stamps? I did, and there are 77 of them, with 13 different denominations and 20 different designs. They add up to $6 and 22.7¢. Overfranked?

The rates in effect on 3/15/93, when the item was mailed, were as follows:

1st ounce, first-class = 29¢

Addl oz, first-class = 23¢

Registration - Value less than $100, insured = $4.50

Registration - Value $100 to $500, insured = $4.85

Registration - Value $500 to $1,000, insured = $5.25

Registration - Value $1,000 to $2,000, insured = $5.70

I don't remember either the value of the contents, or its weight, so some detective work is required. One can tell by that lone 1¢ stamp that the sender was determined to get as close to the exact postage required as possible, so I would assume there is some combination of postage and registration fee that adds up to $6.22, leaving 0.7¢ excess. If the weight was 1 to 2 ounces, and the value was between $1,000 and $2,000, the postage would have been 52¢, and the registration fee $5.70, for a total of $6.22 - Bingo!

And I know it broke the guy's heart to waste the 7/10's of a penny.

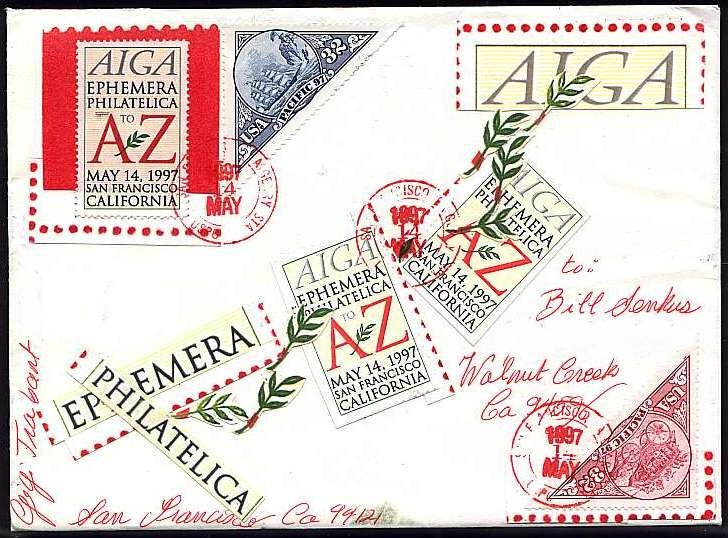

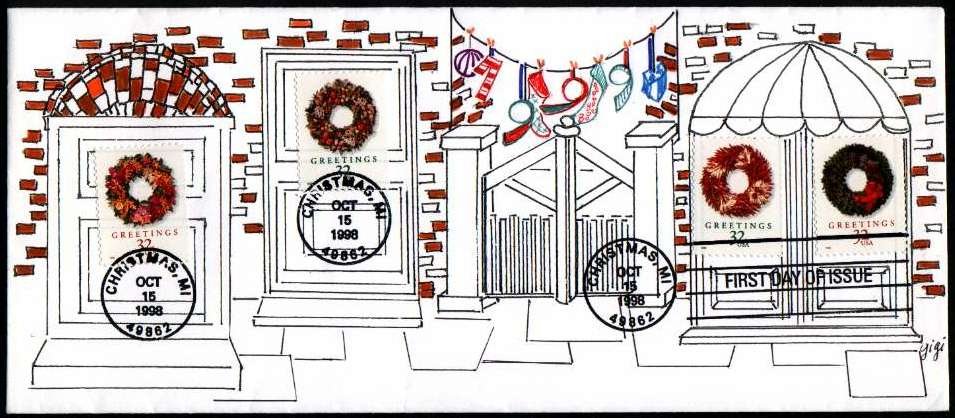

Over-franking can be Fun!

Finally, I have to share the covers above, created by a friend simply to entertain and

delight. I have shown other creations of hers here and here, and add these

just to show that sometimes getting the postage right doesn't matter. The rate in effect

at the time all of these were mailed was 32¢, so the first is overpaid by 32¢,

the second by 8¢, the third by 1¢, and the last by 96¢! That last one is

also an official First Day Cover for the stamps on it, though, which helps excuse its excess.

By the way, the first two covers, postmarked on May 14, 1997, have special significance and value to me because that was the date of our first slide show, and the "A to Z" cinderella on them was part of the invitation to that event, so these are "First Day Covers" for our project, and among fewer than ten such covers that exist!

| Home | O is for Overprint <<< | Contents | >>> P is for Persian Rug | Credits |

All text Copyright © 2000, William M. Senkus

Send feedback to the webmaster: CLICK HERE

Revised -- 02/28/2007