Z is for Zeppelin Post - Page 2 |

|

|

|

|

THE AGE OF THE ZEPPELINS - 1929-1937

THE GRAF ZEPPELIN

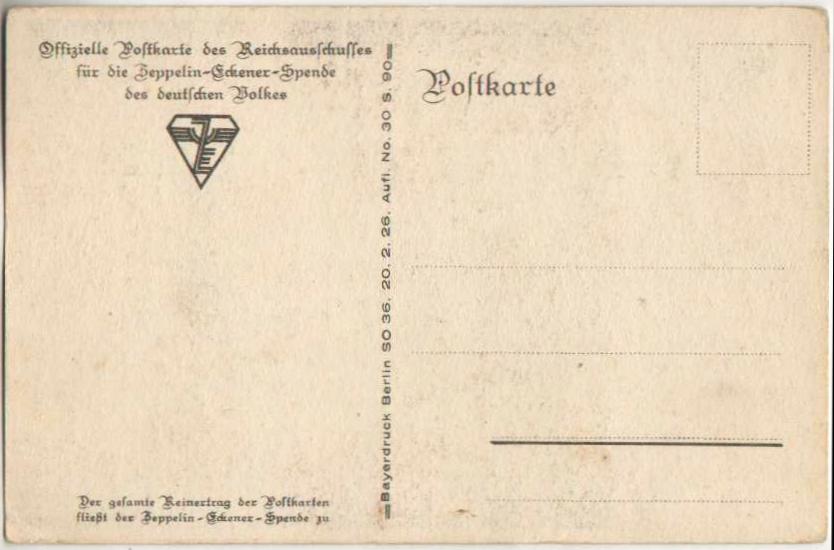

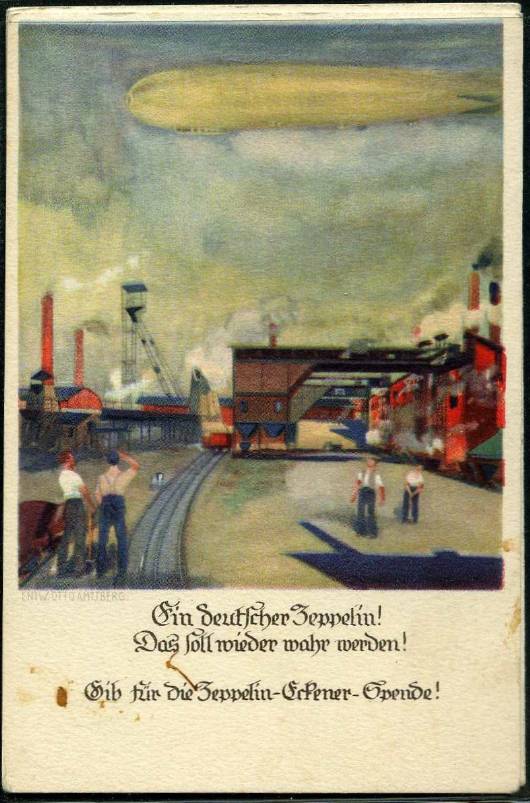

Zeppelin-Eckener-Spende

1926 - Zeppelin-Eckener Fund

Hugo Eckener, his enthusiasm for the airships rekindled by construction of LZ 126, found a way

around the ban against Zeppelin construction - there was no prohibition of private efforts!

In 1926, he

appealed to the German people for funds, and they responded with enthusiasm. His campaign included

souvenir postcards (two at left above), pins (one shown center), medals, and

three souvenir stamps (at right) - 10pf red for contributions from "The German People", 5pf green for

"German Women", 5pf blue for "German School Children" -

and was a resounding success. The Graf Zeppelin, LZ 127, was the result, and Zeppelins were reborn.

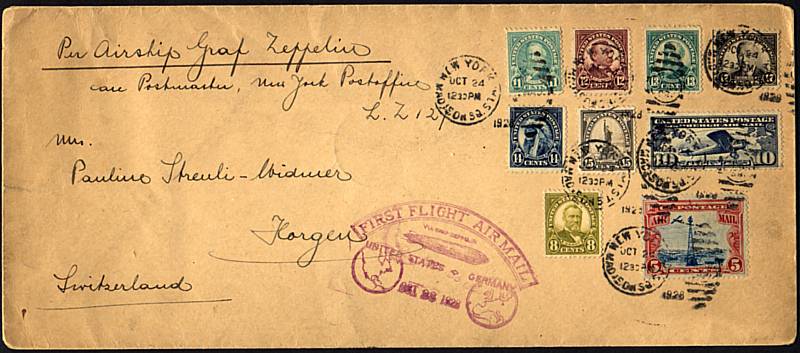

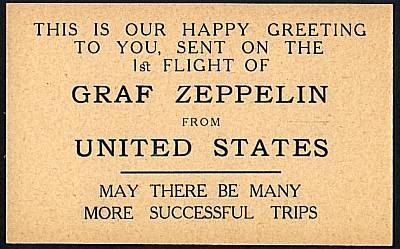

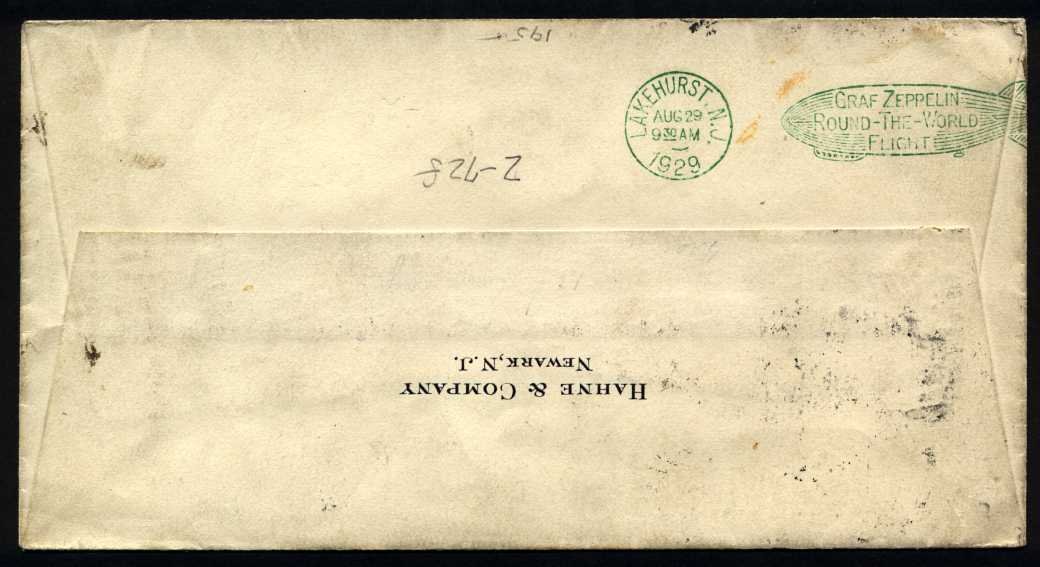

The Graf ("Graf = "Count") Zeppelin, LZ 127, was the longest-lived and most famous of the Zeppelins,

making 590 flights and traveling over a million miles in its lifetime from 1928 to 1937. The Graf

made the first commercial trans-Atlantic crossing in October, 1928. The cover above and the two

below are all souvenirs of the return journey from the US to Germany. Note that the one above has

$1.05 in postage, while the other two have $1.10, the difference being the domestic air mail postage

from their sources to Lakehurst.

Profits from mail were critical to the survival of the Zeppelins. Hugo Eckener, in charge of the

Zeppelin Company by this time, was a shrewd businessman and salesman, who knew how to exploit the

popular excitement about his airships, and provided interesting and attractive special cancels for

all flights. The company received at least 50% of the postage fee for Zeppelin mail, and charged

rates that were astronomical for the Depression-era economy, but still managed to attract enough

customers to stay alive. As you can see from the three above, many were simply souvenirs.

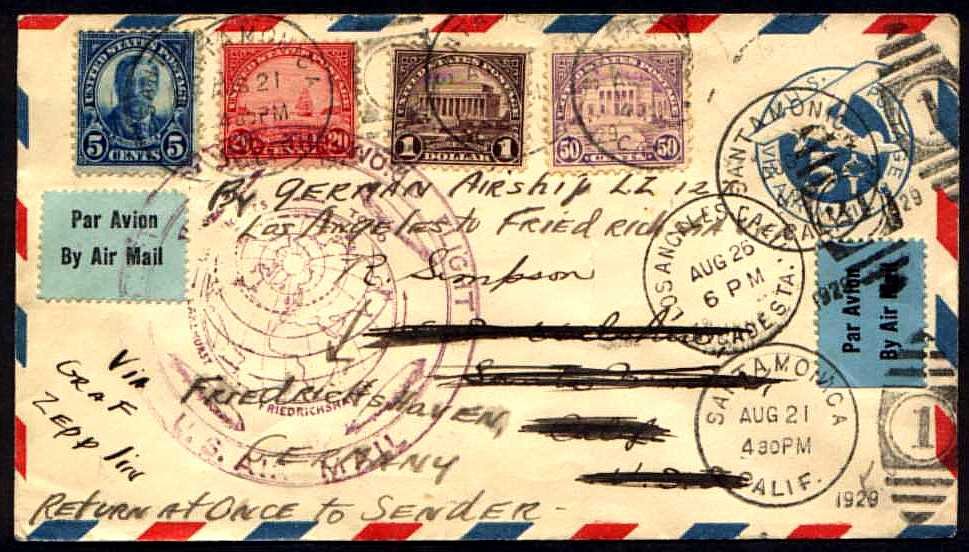

It demonstrates how important the US and philatelic mail were to the success of the Zeppelins that

the flight mentioned above, which arrived in the US in August, 1929 after an initial delay of three

months, was the first leg of the Zeppelin's First Round-the-World flight. But rather than start

east from Friedrichshafen, the Zeppelin first traveled west to the US, so that it started from

Lakehurst, collecting passengers (and mail) there, and traveled back to Friedrichshafen, then to

Tokyo, Los Angeles, Lakehurst again, and back once more to Friedrichshafen. Collectors eagerly

prepared souvenir covers for all or part of the flight.

Postage rates were as follows:

| FROM | TO | CARDS | COVERS |

| Lakehurst | Friedrichshafen | .53 | 1.05 |

| Lakehurst | Tokyo | 1.03 | 2.05 |

| Lakehurst | Los Angeles | 1.78 | 3.55 |

| Lakehurst | Lakehurst | 1.78 | 3.55 |

| Los Angeles | Lakehurst | .30 | .60 |

| Los Angeles | Friedrichshafen | .90 | 1.80 |

| Lakehurst | Friedrichshafen | .60 | 1.20 |

|

Table reproduced from Handbook of Zeppelin Letters, Postal Cards & Stamps 1911-1931, by Berthold and Kummer, 1931, reprinted by Postilion Pubs)

Here's a nice cinderella I found on eBay recently,

advertising the postal rates for the first Lakehurst to Friedrichshafen flight:

It's interesting to note that the rates for the second Lakehurst to Friedrichshafen flight,

at the end of the journey, were higher, presumably because that was the triumphal return home.

|

|||

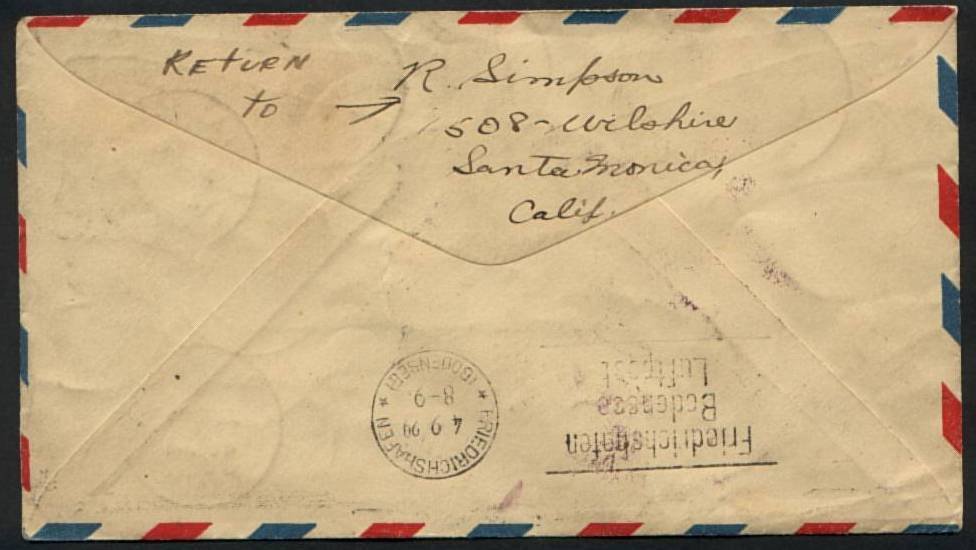

The cover above made the full Round the World journey from Lakehurst to Lakehurst, and appears to be overfranked by 12 cents ($3.72 total postage!) I assume

the sender would have had to pay the 5 cent airmail postage from Newark to Lakehurst, so that would

bring the required postage to $3.60. I see no evidence of other special services, so conclude the

sender just preferred this combination of stamps. They are all from the definitive series then in

use, and all the higher-value horizontal format, which would have dictated against use of the 5-cent

value in place of the 17-cent. On the other hand, a $2 stamp, plus two 50-cent stamps and two 30-

centers would have done the job. Perhaps Mr. Titus simply had to work with what was at hand. A

very attractive cover, with a much clearer strike of the large purple cachet than the following

cover.

Was the sender of this cover confused about the proper way to address it? I assume that all he

wanted was a souvenir of the flight, to be returned to him after travelling from Los-Angeles to

Friedrichshaven (the last two legs of the flight) on the Zeppelin, so he addressed it to himself,

with the notations on front and back "Return to sender". Was he told at the Post Office that this

would accomplish nothing except have the letter delivered straight back to his mailbox, and the

correct approach was to address it to himself in Germany? Hence the scratched-out address. Then

again, it may have been the clerk who was mistaken here, as most such covers I have seen use the

"address-it-to-yourself" approach successfully. First-class postage has always included free return

to sender if undeliverable at its destination. Maybe the rules simply hadn't been worked out yet -

this was only the second journey of the Zeppelin in the US. Or maybe the sender decided at the last

minute to take the trip himself, and collected the cover in Friedrichshaven. I guess we'll never

know. (Total postage = $1.80, which is the correct amount by the table above.)

12/09/05

Above, scans contributed by visitor Michael Cummings, who writes:

I thought you might be interested in seeing another post card that travelled on the Graf Zepelin.

This was sent to my grandfather back on Aug 7, 1929.

Thanks, Mike, I especially like the statistics in the newspaper clipping, though I wonder if the headline was meant to read "Highlights" rather than "Highlands."

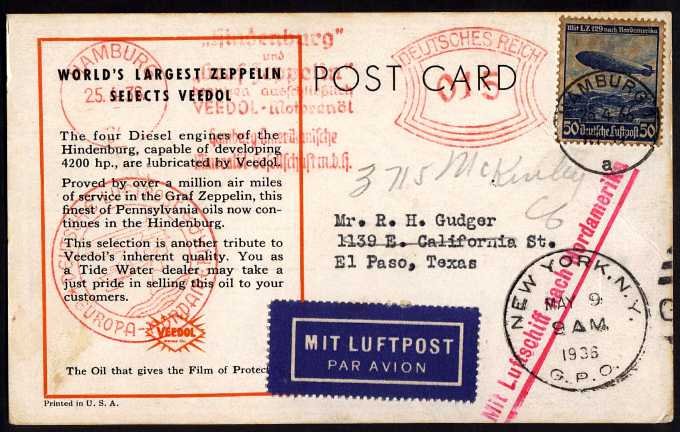

THE HINDENBURG

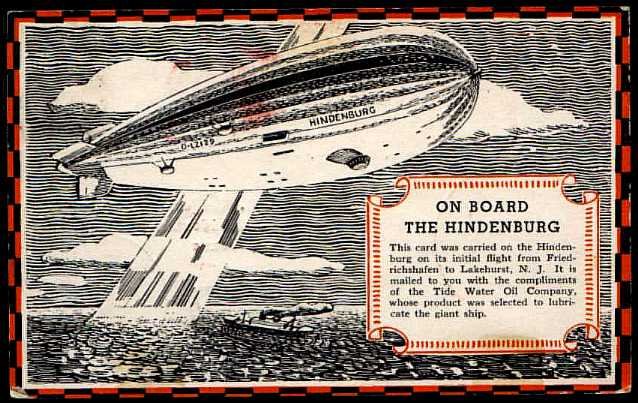

Encouraged by the success of the Graf, Eckener's company built the ultimate Zeppelin, the Hindenburg, which made its first flight to the U.S. in 1936. The card below was carried on that flight.

There were 13,000 copies of this card produced, in two versions, to

advertise the American oil used to lubricate the Zeppelin's motors - "World's largest

Zeppelin Selects Veedol". Both versions are the same on the picture side, but the

text on the address side differs.

The Hindenburg was put into service in March of 1936, and made its first voyage to the US in May,

exactly a year before its tragic crash. It had been built as the ultimate airship, the first truly

commercial Zeppelin, and was intended for use with helium (which is NOT flammable), but the US had

the world's only means of producing that at the time, and refused to sell it to the Germans, for

political reasons, so Hydrogen, whose dangers were no secret, had to be used instead. Until

fairly recently most experts believed it was the Hydrogen that caused the Hindenburg disaster,

but recent research has proven otherwise. Read on.

Click on image for enlarged version

Then we have this very dramatic zeppelin flight cover prepared by Ludwig Staehle, a very popular and prolific First Day cover cachet artist who worked for many of the FDC companies from the mid-1930's through the early 50's. This is one of a set of about twenty-five covers - each apparently unique, and all apparently prepared for Staehle's private collection - that surfaced in the Superior Stamp & Coin auction of June 23-25, 1997. Most were for Zeppelin flights of 1936, and this was the most admired of the group, in spite of its swastika, which I confess I find disturbing, since it suggests that Staehle was a Nazi sympathizer. It sold for $1575 plus a 15% buyer's commission, against a pre-sale estimate of $500 to $750, though estimates for unique material are somewhat meaningless.

Staehle was born in Germany in 1893,

immigrated to this country in 1927, and died in 1967. A talented commercial designer and artist

with many distinguished non-philatelic credits, he seems to have done cachets more out of his love

of the hobby than for any need of the income from them.

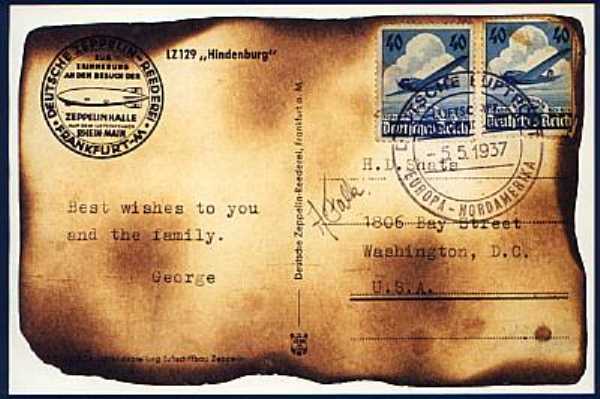

THE CRASH OF THE HINDENBURG - MAY 6, 1937

The card above made that last, fatal trip on the Hindenburg. Cancelled on-board a day before the arrival in Lakehurst, it is perhaps the finest of only about 170 such postal items that survived - it last sold for over $4,000.

OOPS! This just in - Dieter Leder, an advanced collector and exhibitor of Zeppelin material, has informed me that the item above is a forgery! His article about the research that exposed the fake was available for a while on the Internet, but Sandafayre, who used to host society web pages, dropped that service.

Why did the Hindenburg crash?

Eckener and his company had many years of experience behind them in dealing with the risks of hydrogen on their airships, and had incorporated many safety features into their latest creation. Did they get careless? Or was sabotage involved? Recent research indicates that the villain was not the hydrogen gas inside the airship at all, but the paint used on its exterior! Still, as I said at the start of this page, I think Zeppelins were doomed from the start. Airplanes were already taking over even in 1937, and the development of airplane technology during WWII would have ended the Zeppelin saga, crash or no.

Hallvard Sletteb , a collector and Scouting enthusiast in Norway,

has an

excellent web site about Scouts on Stamps,

with a fascinating page about Scout franked Hindenburg crash mail,

including an excellent general discussion

of the Hindenburg and its disastrous end, and images of AUTHENTIC Hindenburg crash covers.

| Home | Z - Page 1 <<< | Contents | >>> Z - Page 3 | Credits |

All Letter images Copyright © 1997, 2000, SF chapter of AIGA

All text Copyright © 2000, William M. Senkus

Send feedback to the webmaster: CLICK HERE

Created -- 05/01/2000

Revised -- 03/04/2006