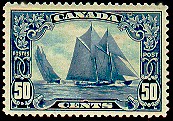

Bluenose - Classic Canadian stamp issued in 1929, and

generally considered the most beautiful Canadian stamp

ever produced, with the perfect combination of design, engraving, and color. I

think it

is one of the most beautiful worldwide.

Centering

"Centering" for a stamp refers to how well the design is centered relative to the

perforations. Most stamps have a rectangular design, with a blank area around it,

and

then the perforations. In modern stamps the design is usually well centered, but in

older stamps, especially those produced before 1900, centering was often quite poor.

Here are some examples:

Those four stamps were printed in 1861, 1868, 1863, and 1868 (l to r), and exemplify

pretty well the extremes of centering that were not uncommon at the time.

Centering is usually described by philatelic experts with initials such as F, VF,

XF.

Here are the terms used, and their general meanings:

G = GOOD. This means the stamp is seriously off center, with the perfs

cutting

into the design. For anything but the rarest stamps, where there are so few that

any

condition is acceptable, stamps with GOOD centering are considered little more than

space

fillers. Some people call this grade AVERAGE.

F = FINE. This means noticeably off center on two sides, but the perfs

touch the

design only slightly or not at all.

VF = VERY FINE. This means the stamp is well centered, but not perfectly

so. It

is a bit off center in at least one direction, but still attractive.

XF = EXTRA FINE. This means the stamp is perfectly centered.

Note that the worst centering is not called POOR or ABYSMAL, which would be far more

accurate. Descriptions are always at least a bit exaggerated.

SO WHAT ABOUT THE FOUR STAMPS ABOVE?

The second and fourth have G centering, the first I would call VF, and the

third I would call F. This is not a science, and has a big effect on a stamp's

value, so

a seller is almost certain to evaluate the centering of his stamps better than a

buyer.

You will see grades such as F-VF, meaning FINE to VERY FINE, and implying that the

stamp is not quite VF, but certainly better than just F. On such minute

distinctions

rest big bucks. There is also SUPERB! And let's not forget GEM! Those imply the

Best

of the Best, a stamp that is the finest imaginable for its issue, and a true GEM

can sell

for many multiples of its catalog value.

"For its issue" - that brings up one last important point about centering. In those

early days when centering varied so wildly, some stamps that were printed in small

quantities, or with very narrow margins,

simply don't occur with centering even as good as VF. SO you will see

descriptions such as "XF for this issue!" attached to stamps that are really only

F. The

seller is trying to tell you this is about the best you'll get. If you trust him,

fine.

I suggest you look up the stamp in

Datz's The Buyer's Guide. He gives precise

statistics about all the early US stamps, with illustrations of typical centering,

so you

can be your own judge of how well a specific stamp compares to the standards for its

issue.

Here's more about centering, and its effect on a stamp's value.

Center Line Block

The center line block is a block of four from the center of a sheet of early 20th

century US stamps, with horizontal and vertical guidelines running through the

perfs, or

through the center of the blank space between the stamps. It was used for two

different

purposes on flat plate engraved stamps of the U. S.

On single-color definitive stamps, which were printed in sheets of 400 (20x20), the

guidelines showed where the sheet was to be cut into panes of 100. We have center

line

blocks because unperforated sheets of many definitives in the years from 1906 to 1926

were sold to private parties for conversion to coils (see the plate diagrams on my K is for Kansas City Roulettes page -

everything

you see on the left-hand image there would have printed.)

Bi-color stamps like our first airmail stamp, the 24¢ Curtiss Jenny stamp of

1918

(Scott C3), were printed in sheets of 100, and had to be printed in two steps, one

per

color. The guidelines helped align the plate for printing the second color.

Unfortunately, they did not guarantee correct up vs. down orientation, and the plates

used for the first printing of the 24¢ Jenny had no other markings to help

show top

vs. bottom. Under the pressures of time and efficiency, at least one sheet was

printed

with the centers inverted. After that sheet of 100 of the Inverted Jenny was

found, TOP

was added to both plates for subsequent printings. (see my I is for Invert Error page for a picture of the Inverted Jenny.)

Civil War

If you grew up in the South, as I did, you know that the proper term is not "Civil

War",

but "The War Between The States".

"CSA" stands for Confederate States of America, the official name for the South

during

the War.

In the North, the official name for the Civil War was "The War of the Rebellion"!

The Internet is full of great Civil War web sites - try your favorite search engine.

Here's a fascinating page titled The Confederate Postal Operations - Adding Order to a Time of

Chaos and

Disorder(!)

Examples of some Civil War era postal material can be found on my own W is for War, A is for

Advertising Cover, and Trains on

U.S.

Advertising Covers and Patriotic Covers pages.

Commemorative stamp

A Commemorative stamp is one issued to honor a person or event. It is printed

once, in relatively small quantities (typically 50 to 100 million in the U.S.), and

withdrawn from sale (if not sold out) after a specified time, usually about a year.

Or

at least that's what it used to be - these days, with stamps for insects,

aquariums, and

dinosaurs, the definition has been stretched quite a bit. They usually make at

least a

pretense of a connection to U.S. history or culture, but let's face it, the name of

the

game is "market appeal". Here is a page with

images of some U.S. commemoratives.

Cover

A cover is any postally used envelope, usually with an address, a stamp, a

cancel, a postmark, and perhaps other postal markings. Many of my pages show

examples of

covers - try A is for Advertising Cover.

Definitive stamp

A definitive stamp (as opposed to commemorative, special, or service-specific stamps) is one

issued as

a work-horse of the postal system. Usually small in size (so many will fit on a

pane),

and with a patriotic (e.g., a flag) or generic (e.g. "Transportation") design, it is

printed in huge quantities (billions), and reprinted as needed (unlike a

commemorative,

which usually gets only one printing), and may stay in service for many years -

some in

the U.S. have lasted over two decades.

Durland Catalog

The Durland Catalog is published periodically by the United States Stamp Society (formerly the Bureau Issues

Association), and lists all known plate numbers on U.S. stamps. That may seem like

useless information, but in fact has several important uses for collectors. For one

thing, its plate number can be used to authenticate a stamp, since plate numbers are

unique to a design and (usually) format. For another, some people collect plate

blocks,

i.e. the

block of four (or on some older issues, six or eight) stamps adjacent to the plate

number, and need to know what plate numbers were used, and in what quantity, since

rarer

numbers command a high premium.

If the topic of plate blocks interests you, I've written a little about them, here

Expertizing

I've made reference throughout these pages to the presence of fakes and forgeries

in the

philatelic marketplace, and the importance of being cautious when buying expensive

material - see especially Q is for Quality.

An expertization certificate is a form of insurance. Someday you or your heirs will

want to sell the items you have collected, and a certificate helps guarantee that a

prospective buyer will be willing to pay some reasonable percentage of what you did.

The way you obtain a certificate is fairly simple - first you need a request form

from

the service you wish to use. There are several general expertizing services I know

of in

operation in the US right now, and many other specialized ones. The next section

of this

document gives the names and addresses of two of the major ones. Write for a

certificate, which will explain as well the terms. They all charge a fee, either a

percentage of the item's value, or a flat fee per item.

Follow the instructions on the form, and send it in, then be patient. These things

take

time. Four to six weeks is typical.

A certificate is not a guarantee, however; new technology and information have led to

revised opinions about some material, in both directions - items once judged

authentic

may now be judged fakes, and ones rejected as fakes may be accepted as valid,

though the

latter is far less likely - you can count on the experts to be cautious and

conservative -

if they are not sure, they will say so, and give a "No Opinion" certificate.

The most frustrating thing for me about getting a certificate is that it never says

exactly how the experts reached their decision. Depending on the item, its value,

and

the complexity of the judgment, a service will submit your material to just one

expert,

or to as many as three or four. Most services have a reference collection of

material

known to be both genuine and fake, for comparison with items submitted for

expertization.

Some also have sophisticated modern equipment that allows them to analyze the item

with

special light or to analyze it chemically to reveal key features. And you may

assume the

experts have seen a lot of real items and fakes, so they know what to look for.

The bottom line for me is this:

1. I always try to authenticate tricky material first myself, if only to learn a

little

more about it. Understanding how to expertize my own material and what makes the

difference between the real thing and a fake increases my enjoyment of the hobby, and

helps protect me from costly mistakes. In addition, if I find it difficult to decide

what something is, I am better able to appreciate the efforts of the experts I

consult.

2. I avoid questionable material. If I have trouble finding the feature that

distinguishes a variety - a watermark or design element, for instance - I pass the

item

by. Even if the experts say it is genuine, I prefer to own something that exhibits

its

distinguishing marks as clearly as possible. This does not mean I don't need a

certificate for that item, of course. If there's money to be made faking it, someone

will do it.

Expertizing Services

American Philatelic Expertizing Service. Go to their website, or write them at -

APES

P.O. Box 8000

State College, PA 16803

American Philatelic Society members get a discount from the APES, so joining that

organization can save you money if you need a lot of certificates.

One excellent source of information about how expertizers work, and the methods

that are

used to authenticate stamps, is the recent series of articles by Mercer Bristow,

Director of the APES, in Stamp Collector (which is sadly now defunct (7/4/4).

-----------------------------

The Philatelic Foundation is one of oldest collector organizations in the

country. It has one of the best reference collections in the world, and offers one

of

the most respected expertizing services. There is another organization called the

"American Philatelic Foundation", which does have a web site - it has no connection

with

the PF.

The Philatelic Foundation

70 West 40th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10018

Telephone: (212) 221-6555; Fax: (212) 221-6208.

Email: philatelicfoundation@verizon.net

Web site

-----------------------------

The Confederate Stamp Alliance specializes in CSA material.

Applications for authentication and/or applications for

membership are available from:

Patricia A. Kaufmann,

CSA Recording Secretary

522 Old State Road

Lincoln, DE 19960-9767

Link to Web site

First Day Ceremony Program

Most stamps issued by the USPS are announced several months in advance, with a

specific

issue date and city or town of release. At the designated place and time, a First

Day

Ceremony is held - some are very simple, others quite elaborate. Official USPS

Programs

are handed out free to attendees at the First Day ceremonies. These programs - which

also vary from plain to fancy - always contain a copy of the stamp being released,

with a

first day cancel, and a list of the dignitaries attending. The programs are a

moderately

popular collectible, and most are quite affordable, with prices in the $5 to $20

range.

The most desirable copies are ones that have been autographed by the famous names in

attendance. I have one I prize from the 1997 Thornton Wilder stamp FD ceremony with

Carol Channing's autograph - she starred on Broadway in "Hello Dolly", which was

based on

a Thornton Wilder play, "The Matchmaker". For some stamps issued in the past few

years,

the programs have been available by mail from the USPS Philatelic Fulfillment

Center, but

as with many practices of the USPS, there is no consistency to this. Recently

(starting

mid-2000), the ceremonies and programs have been severely down-scaled, as part of a

USPS

economy drive. The programs are now mostly very plain and unadorned.

Free Frank

The term "free frank" is often used today to describe the privilege granted to all

Congressmen, to send their mail free of postage. They simply sign the cover where

the stamp would go, or stamp their signature there.

But "free frank" is actually redundant,

since the verb "frank" means (according to my dictionary) "to mark (a letter,

package,

etc.) for transmission free of the usual charge, by virtue of official or special

privilege". Presidents, members of Congress, Postmasters, and other government

officials have long had this authority - their signature serves in place of a stamp

to

prepay their official mail, so one says they have the "franking privilege".

A more appropriate use of the term "free frank" is when applied to soldiers' mail -

in

most wars since the US Civil War, soldiers on active duty could send mail without

postage

by writing either "Soldiers' Mail" or "Free" in the top right corner. One of the

many

valuable accomplishments of the Universal Postal

Union was the institution of this Free Frank privilege for servicemen in time

of war

and the unobstructed passage of such mail between combatants, though the

implementation

of this system has not always worked smoothly.

Click here to

view a page about the history of the

franking privilege.

Freshness

"Freshness" is one of the important factors in evaluating a stamp's condition. Some

others are GUM, CENTERING, and PRINTING.

The ideal stamp is "Post Office fresh!" meaning it looks just as good as it did

when it

was first purchased, or better yet, when it was printed. The paper is fresh and

soft,

not browned or brittle; the gum is fresh, not browned and cracked; and the image is

clear, crisp, and unfaded. All of those elements combine to define a stamp's

Freshness.

Sometimes you have to look at a lot of examples of a stamp, to appreciate what true

"freshness" is. A stamp may look faded, but that could be just the way all of the

issue

was printed. The paper may look toned, but that could be just the paper it was

printed

on. So you have to look at a lot of stamps before you can safely evaluate just one.

Grills

"Grills" are a sort of embossing that was applied to US stamps as a security measure

during the period from 1867-1872. All or part of the surface of each stamp was

impressed

with a grid of small indentations that were intended to break the surface of the

paper

and cause it to absorb a cancellation so that it could not be washed and reused.

This was but one of many such schemes attempted by the USPOD in this early era of

postage stamp production. Whether they were really necessary - or merely the

result of

someone's paranoid fantasies - is debatable. None of them proved worth the time and

trouble, nor lasted long.

GUM - Hinging - Gum Condition

It surprises many people initially when they learn that the condition of the gum on a

stamp affects its value to a collector, but it's true.

Think of it this way - while it seems silly for a stamp worth only a dollar or two,

if

you are going to spend a hundred dollars on a tiny scrap of paper, you should get the

best example of that scrap of paper you possibly can. And stamps worth a hundred

dollars

- and much more - are not uncomon. Therefore the ideal stamp is post-office fresh,

with

bright color, a crisp, perfectly centered design, sharp perforations, and fresh

unmarred

gum. With early stamps, most of which have suffered some sort of wear over the

years,

small variations in each of those features can have significant affects on the

value (see

Q is for Quality)

Stamp Collectors have developed a special vocabulary to describe hinging on stamps -

NH means "Mint, Never Hinged", and is often indicated (in auction catalogs,

for

instance) by a pair of asterisks (**). It means the stamp is unused, and its gum has

absolutely no disturbance of any sort. Post Office fresh. You will often see

"MNH", for "Mint, Never Hinged", but to me that is the same as "NH" - the

"M" is

just for emphasis.

LH means "Mint, Lightly Hinged", and is often indicated (in auction

catalogs, for

instance) by a single asterisk (*). It means the stamp is unused, but has been

hinged,

and the hinge removed, leaving a discernible mark on the gum, but only a slight

one. You

may see "VLH", for Very Lightly Hinged, implying that the trace of hinging is being

mentioned only for strict accuracy.

H means "Unused, Hinged", and usually implies a good deal more than just

lightly

hinged, i.e. there are probably hinge remnants on the stamp.

HR means "Unused, with Hinge Remnants", and you can be fairly sure the back of

the stamp is a mess, with heavily disturbed gum and parts of several messy old

hinges.

OG means "Original Gum", and is often used to avoid more precise terms. It

means

the stamp is unused, and has at least some of its original gum, but is probably

hinged or

heavily hinged. You may see "partial OG", meaning the stamp has lost most of its

gum

somehow, but still has a little. Terms like OG are salesman's terms, ways of

trying to

make a stamp look better than it is.

DG is sometimes used as well, and means "Unused, with Disturbed Gum", which

does

not mean the stamp needs a psychotherapist, but that the gum is not pristine, and

none of

the other terms describes its condition accurately. There should be no hinge

remnants.

Sweated Gum and Glazed Gum are basically the same, and describe the result

when

stamps are stored under too much heat and/or pressure, melting the gum into a very

smooth, shiny condition that reduces the value as much as hinging.

Watch out for stamps with hinge remnants and/or heavily disturbed gum, as these can

conceal much more serious defects such as tears, thins, repairs, etc. Any stamp

that is

heavily hinged loses at least half its catalog value at once, and may in fact

qualify as

no better than a space filler. And keep in mind that anyone selling a stamp will

always

try to downplay its defects, so one man's "VLH" may be another's "H". Terms like

"virtually" and "almost" are often used to stretch the truth a bit.

For more on the value of stamps, see my Q

is for

Quality page, and my page on The

Economics of Stamp Collecting.

Locals, Agents, Provisionals, Carriers, Expresses, and

Forwarders

The period immediately before and during the early years of postage stamps in this

country was particularly rich in interesting and often short-lived experiments in

how to

prepay and deliver mail. All the postal mechanics and procedures we take for granted

today - for printing, distributing, selling, and processing stamps and stamped mail

- had

yet to be developed. Home delivery of mail did not exist - one had to drop mail at

and

collect it from designated places. There were not even post offices as we know

them -

collection and delivery points were public meeting places such as hotels and public

houses.

Even after the successful experience with the first postage stamps in Great Britain

in 1840,

the U. S. was not convinced the idea would work here, partly because it required

postal

reform, including lower standardized rates, which many feared would bankrupt the

government. But in 1845 Congress enacted a major standardization of the postal rate

structure, and Postmasters in the largest cities, starting in New York, sought and

received permission to create their own stamps - these were the Postmasters'

Provisionals, which were replaced in 1847 by the first official Government

issues.

During the same period, private and public organizations were developing the ideas

and

tools that would evolve into our modern mail system. Many of them created stamps,

i.e.,

adhesives or handstamps to record the payment of fees. The collection and study of

these

items, on and off cover, is a fascinating and rewarding specialty.

-----------------------------

A local is any private mail-carrying entity, and the term is sometimes used to

cover all the more specific terms discussed below. The true Locals were private

companies operating in larger cities to provide local pickup and delivery of mail

strictly within their city, mainly or at least partly independent of the Post

Office.

Many issued their own adhesives.

Carriers were individuals or companies who provided the missing link between

individuals or businesses and the Post Office - they charged a fee to take mail to

the

nearest Post Office or to collect it from one and deliver it to the addressee. Some

issued adhesives. The early ones were independent, but starting in the early 1840's

many were absorbed by the Post Office

Department. From the 1850's through the 1890's (?) Carrier service remained a

premium

service, even when provided by the USPOD.

Expresses were companies operating over longer distances, between cities, to

provide service in competition with the mails, or to offer services (such as package

delivery before the advent of Parcel Post) the Post Office did not. Their equivalent

today is organizations such as UPS and Federal Express. Their attraction then, as

now,

was the ability to provide faster service. Some issued adhesives to show payment

of fees.

Agents were individuals who acted on behalf of the Post Office, usually in

connection with a boat or train. They collected mail and fees at a departure

point, or

en route, added markings such as "PAID" and other postmarks and

cancellations, and

entered the items into the mailstream. They did not issue their own adhesives.

Forwarding Agents thrived during the period from 1820 to 1860, and served as

the

collecting and routing mechanism for international mails. Many added their own

markings

to the mails they handled. To my knowledge they did not issue their own adhesives.

To learn more about Carriers, Locals, and Expresses, I suggest you start with the

Siegel

Auction Galleries Encyclopedia entry on the topic.

"On piece"

Philatelists use the term "on piece" to describe a cancelled stamp on a piece of

paper,

usually a corner cut from an envelope, and ideally including all of the

postmark/cancellation. A stamp may also be "on cover", i.e. on the entire envelope

it

paid to mail.

Pane vs. Sheet

A pane of stamps is the largest quantity of stamps you can buy at a post office.

Many

people mistakenly call this a "Sheet of stamps", which actually means a larger

multiple,

of four or six or eight or even more panes, and corresponds to the size of the

plate used

to print the stamps.

You can buy full sheets (also called Press Sheets) of many modern stamps through the

USPS Philatelic Services Division, headquartered in the salt caves in Kansas City,

at 1-

800-STAMP-24.

Pasteup

Pasteup is a term used to describe a process used in creation of early coil stamps,

which were created in a manual operation that required trimming and pasting strips of

stamps together to form longer strips. The longest contiguous strip of stamps one

could

obtain at the time was twenty, so every twenty stamps in a coil of stamps there

would be

a Pasteup or Pasteup pair, where two strips had been joined. Some collectors of

early

coils like to collect these as significant varieties, while others avoid them.

For

more information on how pasteups were created, see this.

Perforations - Unperforated vs. Imperforate vs. Misperforated

"Imperforate" means a stamp was issued without perforations, a practice that

was

common in the earliest days of stamps, and again for a period in the US at the

start of

the 20th century, when private companies converted unperforated sheets to coils for

use

in their proprietary vending and affixing machines.

"Unperforated" means a stamp failed to receive the perforations it should have

had, and was released that way by mistake, constituting a production error.

"Misperforated" means a stamp has perforations, but they are so poorly aligned

with the design that they constitute a production freak. The line between "poorly

centered" and "misperforated" is somewhat a matter of personal judgment.

Despite all the above, few people use "unperforated". The common term for a stamp

issued "unperforated," in error, is "Imperf Error". So much for precise terminology.

Plate Blocks

I started collecting when I was eight or ten, when someone gave me a starter set for

Christmas. My Dad's boss heard I was collecting, and started sending home plate

blocks

of new issues. That hooked me - free stamps, and in a format I found mysterious and

appealing. I eventually accumulated a U. S. plate block collection for every issue

from

about 1910 on, and then decided I had too much money tied up in my collection, so I

sold

it off. But I still love plate blocks and other multiples for what they reveal about

stamp production methods and their development.

A plate block is the block of four (or on some older issues, six or eight) stamps

adjacent to the plate number on the pane of stamps you buy at the Post Office. Those

numbers exist on most stamps produced in this country since 1894, when the BEP took over production of U.S. stamps. Prior to that

time, stamp production was performed by private companies, and there was no official

policy about plate numbers, so some sheets of stamps had them, but others did not.

Most

did have some sort of marginal inscriptions, such as the name of the company that

printed

them.

Plate numbers were added to stamp plates as both a security device (sort of like

serial

numbers on money), and as an accounting device (to help in keeping track of how many

times a plate had been used, for example).

The study and collection of plate blocks is an interesting specialty area. Some

people

try to obtain an example of every plate number, while others are content with just

one

per issue. Until a few years ago, plate blocks were relatively scarce, since there

was

usually only one per pane of fifty or one hundred stamps. Recently the USPS has

started

putting a plate number in every corner of even small panes of twenty, so plate blocks

have little scarcity value, and have lost their appeal to many collectors.

The exception to the rule that all stamps since 1894 have plate numbers was the

Overrun

Nations set of 1943, about which you can learn a little more here.

Other pages in my web site where I mention (and show examples of) plate blocks are

F is for Firsts,

H is for Handstamp,

I is for Invert Error,

Durland Catalog,

Knapp FDCs.

Postal Markings

Postal Markings include handstamps, machine markings, hand

notations, x-cancels, etc., i.e. any officially applied

marking on a

stamp or cover, to cancel the stamp or provide some sort of record of its cover's

progress through the mails.

"CDS" stands for Circular Date Stamp, the most common sort of postmark put on

letters to record their time of entry into the mailstream, or of their receipt at

some

point along the way.

"PAID" was a common marking up until 1850 or so. Prior to that time, most

mail

was sent DUE, i.e. the recipient had to pay the postage. In the rare cases when the

sender pre-paid the postage, a PAID marking was applied, usually with the amount

prepaid,

e.g. "PAID 5", for prepayment of 5 ¢. (See the section below on "Stampless

covers"

for a couple of stories about how people used and abused the DUE system.)

"Cancels" today are the bars or lines to the right of the CDS that "cancel"

the

stamp,

i.e. deface it so it cannot be reused. In the 19th century cancels were often either

very

crude blobs that totally obscured a stamp's design, or Fancy Cancels

with wild and wonderful shapes representing anything from a bird to a death's head.

"Postmarks" are the city, date, and time stamps (usually in a circular border,

therefore a Circular Date Stamp), applied to mail to indicate the place and time

when it

entered the mail stream.

PRINTING - Printing Quality

One of the factors in evaluating a stamp's overall condition is the Quality of

Printing.

Especially in the early days of US stamp production, the quality of the product

varied

tremendously. Printing plates were expensive to produce, so they were used as long

as

possible, and the difference in the sharpness of the impression on an early printing

versus that on a late one can be dramatic. Ink was mixed and applied by hand, so the

amount, color and distribution all varied. The best way to understand this is to

look at

a lot of stamps, and see the differences for yourself. The most valuable stamp

will have

a sharp, crisp, bright impression, while its lesser brethren will look faded and

muddy.

Siderographer

Occupational title, engraving - person who operates the machine that transfers dies

to

plates, and supervises mounting and unmounting of plates on presses. Many U. S.

stamps

printed

in the early twentieth century have initials in the sheet margins, sometimes many

sets.

The Siderographer's initials occur (usually) only once per plate, and are

usually

in the

lower

left corner, put there when the process of "rocking in" all the individual stamp

images

was completed. The Plate Finisher's initials were added in the bottom right

corner, and

also occur (usually) only once per plate, as the Plate Finisher did the burnishing

and polishing of the plate after the Siderographer did his job.

Up until 1911, Plate Printers added their initials to the plate as well, one

set

each

time the plate was checked out of the vault for use, so there are often many

different

sets.

The images below are typical examples of plate printers' initials.

I'm not sure why, but the majority of the good examples I have seen

are from the Pan-American Exposition issue of 1901, and primarily for the plates

used to

print the vignettes (center of the design), in black. Perhaps most other plates were

larger, so the initials were printed in a part of the selvage that was cut off and

discarded?

For more on the subject of plate initials, take a look at the

excellent

web site of Doug

D'Avino, at

http://home.earthlink.net/~davinod/Initials.htm . My thanks to Doug for

his assistance in my getting this writeup right - on the subject of multiple

Siderographer initials on one plate, an uncommon but occasional

practice, he wrote me -

There are a couple of instances of multiple Siderographer initials on a plate...

It is

suspected that: 1) The second set of initials came from an apprentice or

2) Schedules were tight so another siderographer finished the job (perhaps

after it was proofed and had to be corrected). On my site, Charles

Vermeule and Harold M. Clarvoe have both initialed a single plate as

siderographers.

Service-specific stamps

Service-specific stamps are ones issued for a specific type of mail, such as

Air-

mail or Priority Mail. They are like definitives, in that they

may be

reprinted as needed, and remain on sale for an indefinite period of time. Today

they can

be used for any mail, their use is not restricted to the service for which they are

issued, but up until about thirty years ago that was not the case - an air mail stamp

could be used only for air mail postage. See also commemorative

stamps and special stamps.

Special stamps

Special stamps are ones that fit into none of the other categories(!) They

aren't quite definitives, they're not commemoratives, and they are not service-specific

stamps. They include Christmas stamps and Love stamps and miscellaneous other

issues

that are printed in relatively large quantities, may be reprinted as needed, and may

remain on sale for several years. Sounds like a definitive to me, but someone

decided

not.

Stampless Covers

The term "Stampless Cover" usually refers (for U.S. postal history)

to mail sent before the introduction of postage stamps

in 1847. Up to that time, letters could be sent either Prepaid or Due - the latter

was

most common - and the amount of postage was marked in pen or with a handstamp on the

letter. Mail carriers had to collect the postage from the recipient if it had not

been prepaid.

The collection and study of stampless covers is a popular branch of philately.

Features

that make a stampless cover appealing are what postal markings it carries, the

source and

destination of the letter, whether prepaid or due, and the rate charged.

WHY ROWLAND HILL INVENTED POSTAGE STAMPS

There is a story that Rowland Hill, the man credited with the establishment of

cheap

postage and the use of postage stamps in Great Britain, was inspired to develop the

concept by

witnessing a scene in a country village - the postman presented a letter to a village

maiden, who glanced at it, then handed it back, saying she could not afford to pay

the

postage. Hill, in sympathy, paid the postage and handed it to her. Once the

postman

had left, the girl confided to Hill that she did not want the letter at all, since

the

message it conveyed was written in a private code on the exterior, and she had read

it

when the postman first handed it to her. Whether the story is true or not, it

illustrates the major weaknesses of the older system, in which rates were very

high, so

most mail was sent Due, and the recipient was under no obligation to pay it.

THE POSTAGE DUE PRESIDENT

Even after the introduction of postage stamps in the U.S., their use was not

mandatory

for eight more years. One famous consequence of this was that in 1848, Zachary

Taylor

did not know he had been nominated for President

for several weeks after the nomination took place, until someone arrived to tell

him in

person - he had refused several letters conveying the news, because he did not care

to

pay the postage due! This seems incredible in these days of instant world-wide

communication, but demonstrates not only the disadvantage of the postage rules in

effect

at the time, but the different attitude of those times - people valued their

privacy. It

must be said as well in the famous man's defense that he had been forced to

instruct his

postmaster to reject all unpaid mail. Taylor was receiving so much from admirers

that

the cost of the postage due was more than he could afford to pay!

Moreover, he had not sought the nomination, and was not expecting it.

The term Stampless Cover applies as well, technically, to any other sort of cover

sent

without a stamp, such as Soldiers Mail and Free Franks, but its use is generally

understood to mean covers from the pre-stamp period.

Prepayment of postage became mandatory in the US in 1855.

Tagging

Tagging is a chemical substance used to coat a stamp (or as a component of its ink or

paper) that reacts to Ultra-Violet light by glowing. The purpose is to make stamps

easier for automated facer-cancellers and sorting machines to detect. The US started

using tagging on its stamps in a test mode in 1963, and since 1974 has used it on all

stamps. Most foreign countries now use some form of tagging as well.

To see tagging on US stamps you need a short-wave UV lamp, which you can buy from any

philatelic supplies dealer. The cheaper lamps, which cost as little as $35, may

require

total darkness to reveal the subtler types of tagging. A more versatile lamp can

cost as

much as $200.

Be very careful when using a UV lamp, as the light can damage your eyes if you look

at

it directly, and the human eye cannot detect UV light, so you will have no warning.

You

should be safe viewing the effects of UV light on your stamps, however, as that is

merely

reflected light.

Some collectors specialize in the collection and study of tagging varieties. In

the early

years of tagging on U.S. stamps there were several different styles in use, including

overall, and blocks of different sizes. Today most tagging is part of the paper or

of

a surface coating on the paper.

Thermography

Thermography is a specialty printing process in which a powder of ink and resin is

deposited on paper and then fused with heat into a raised, usually glossy, enamel-

like

design. It is sometimes mistaken for engraving, which can also produce a raised

design,

especially when printed on coated paper.

Wheel Arrangement Notation System

Some of the train references in these pages include notations such as "4-4-0" in the

locomotive description. These are a shorthand to describe the wheel arrangement of

steam

locomotives. The system used in America is called the Whyte system. There are three

(occasionally four) numbers - the first represents the number of leading or pilot

carrying wheels, the second the number of driving wheels, and the third the number of

trailing carrying wheels. The drivers are usually much larger than the others, and

are

the only essential wheels. So you could have an 0-4-0, but never a 4-0-4! You can

read

more about the

Whyte system

HERE .

The Europeans use a different system, with a combination of letters and digits, and

even

we Americans have a separate one for diesels. You can read more about the European

system HERE

and HERE

.